The (real) shape of the Internet

Facilitator

Depending on the drawing outcomes and the knowledge level of participants, the presentation might need to be adapted (sharing more or less information).

The following image series gives an introduction to what the internet really looks like, beyond the usual diagrams and icons we often see.

Facilitator

If the internet feels hard to understand, that’s because it’s mostly hidden. Hidden because it’s on purpose, not just because it’s complicated. First, because everyone has been telling us that the internet is “immaterial”, “virtual”, “remote”. Exactly like when we search online: clouds, airy drawing, graphs, etc.

Facilitator

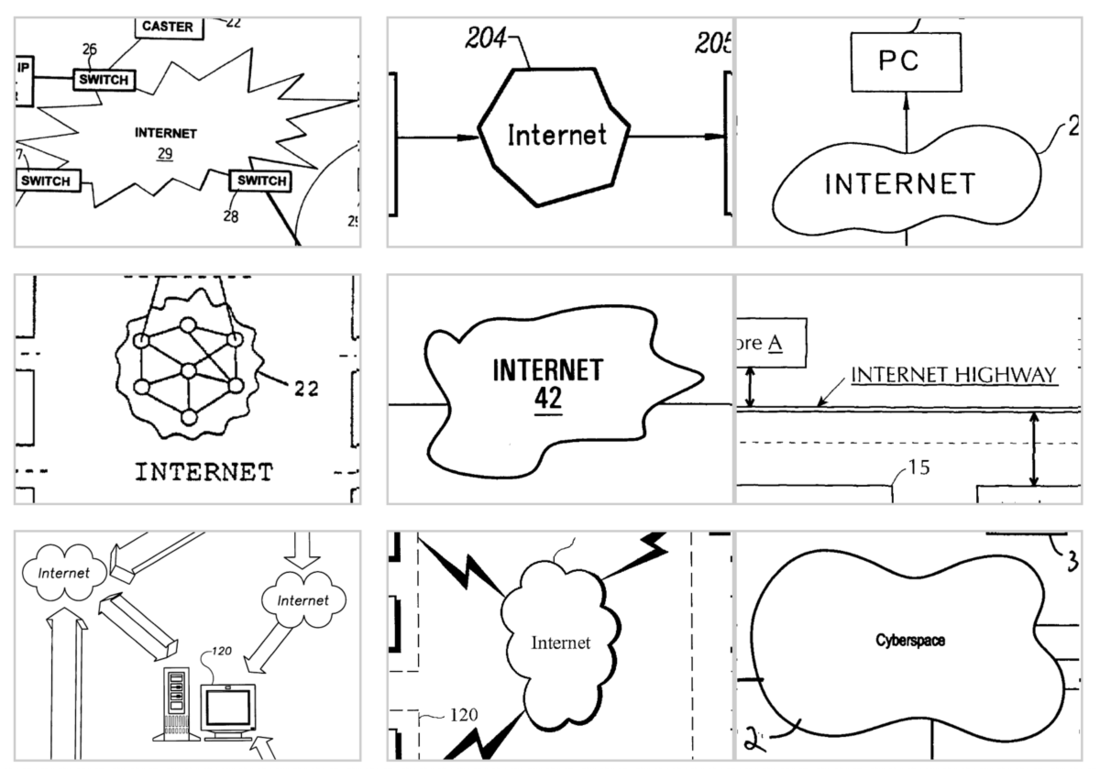

An artist called Noah Veltman summarizes this very well in this drawing collection: the Internet is apparently a “bean” or a “cloud”. But although the internet is a network (that part is true), it definitely is not “light” or “clean”, but rather it’s heavy and dirty. Let’s see why.

Facilitator

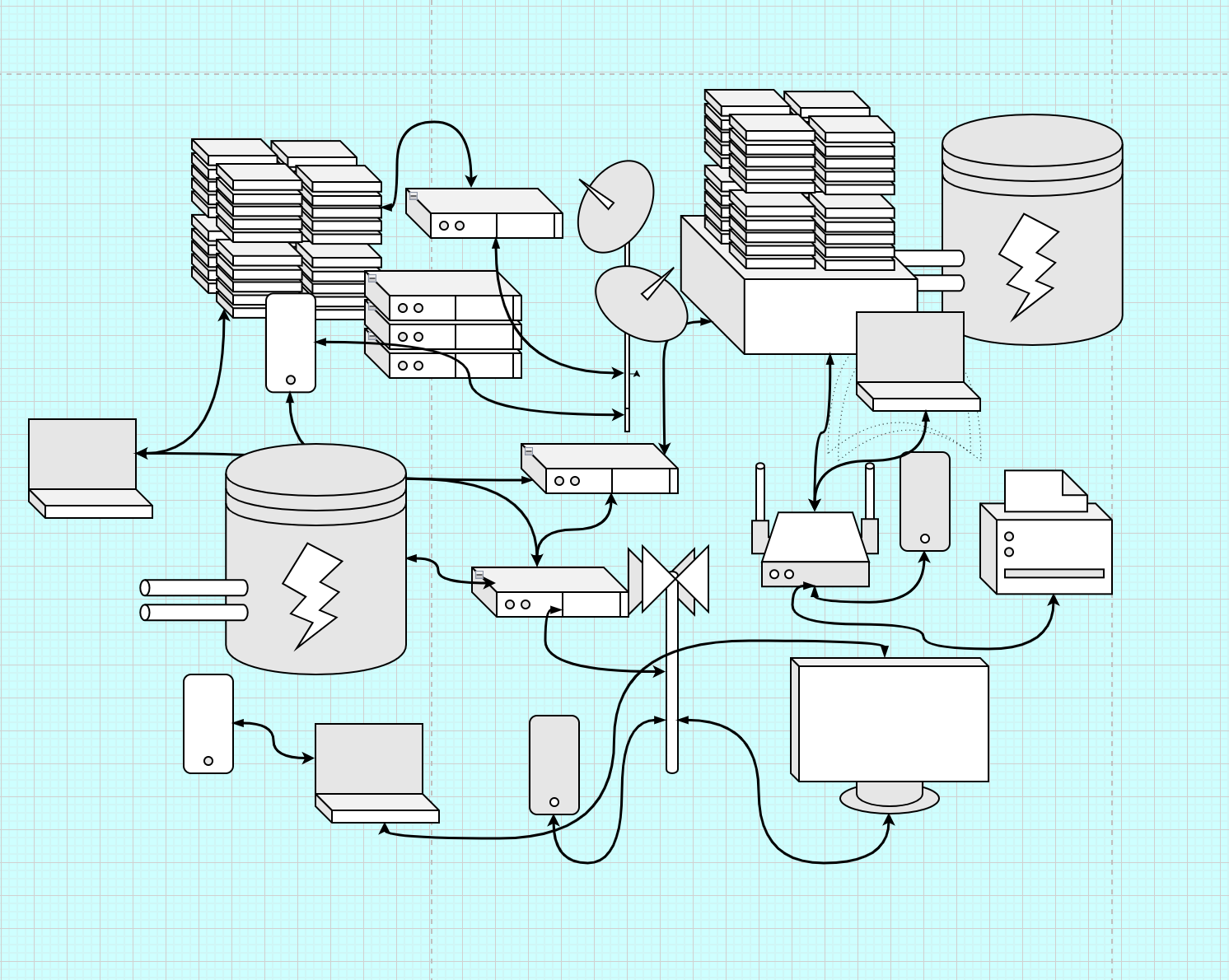

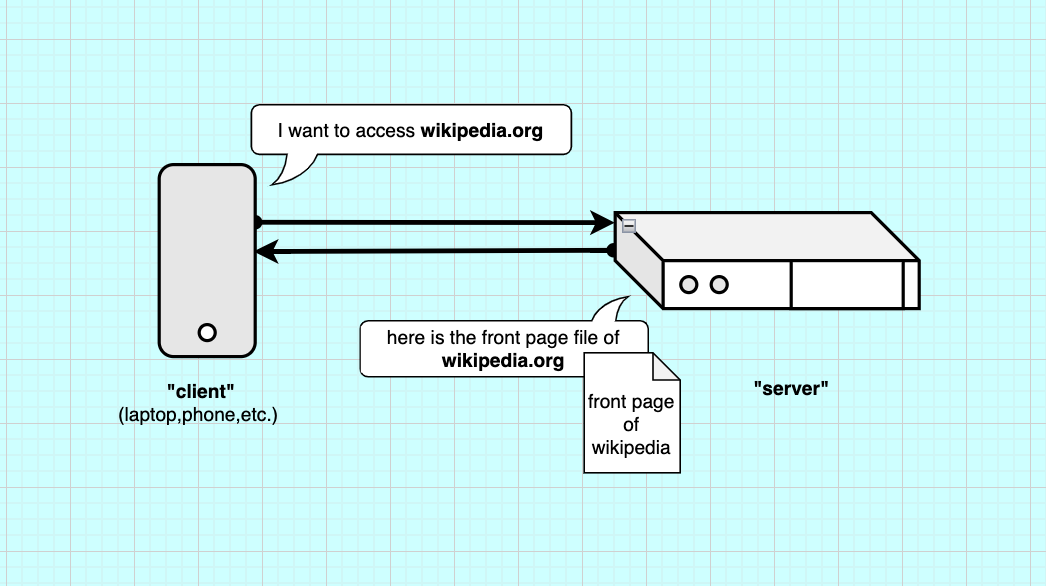

What the web really looks like: A/ Abstractly—like an this illustration— it’s a network of computer networks. Different types of computers: 1-Servers, to serve contents 2-Clients: computers retrieving content (phones, laptops, game consoles, TVs, but also bankcard machines, smart fridge, surveillance cameras, road radars, etc.)3-DNS (aka Domain name servers): to point clients to servers, but also switches, exchange points, etc. 4-All the infrastructures that supports those connections: power plants cables, antennas, etc.

Facilitator

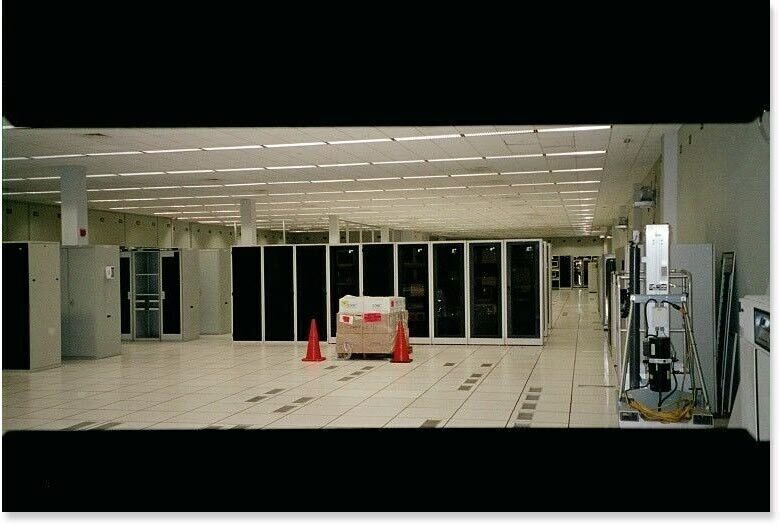

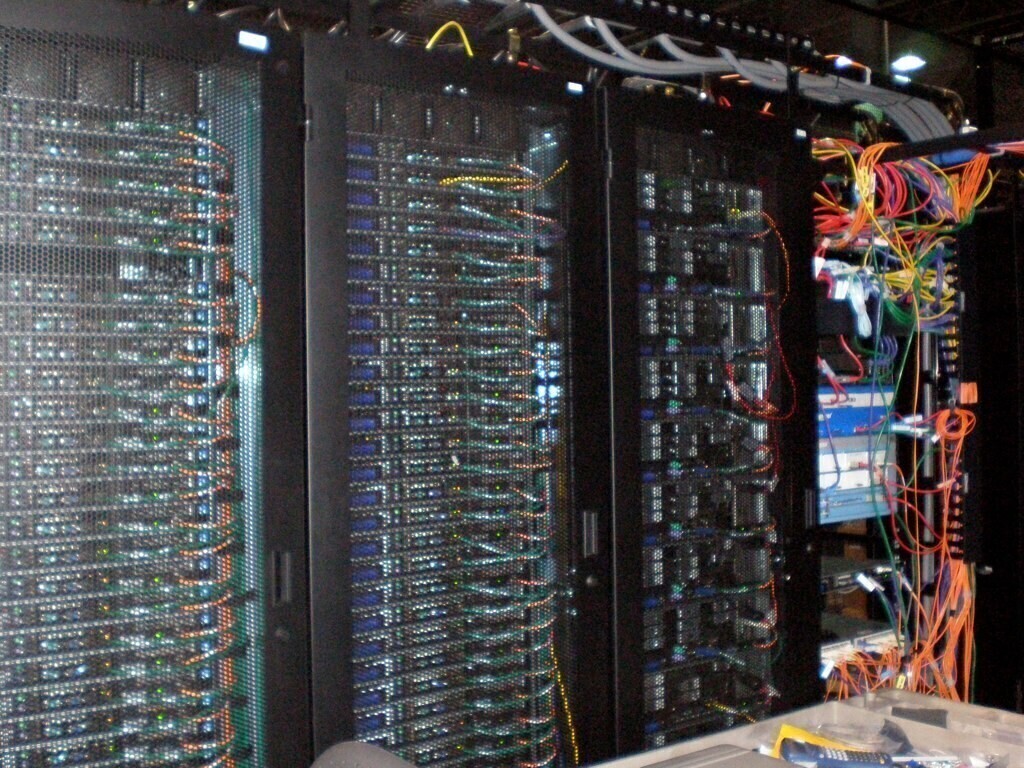

All of this infrastructures: it’s very tangible, and it’s around us. Most of these computers/servers : they live in data centers. Datacenters are buildings housing computers, equipped with cooling systems, energy systems, etc.

Facilitator

These data centers: not only in the US. Everywhere and more and more, especially since AI is becoming so important. Image above is from the Datacenter cluster north of Amsterdam, in Agriport. Neighbors to industrial farms, producing tomatoes and peppers all year long. Datacenters are as big and impactful as any other factory.

Facilitator

Inside: looks like that: rack servers (shelves full of computers), all connected together to add up their power/speed. Those computational processes produce a lot of heat.

Facilitator

All these computers in datacenters need to be connected to our devices at home/office. Internet is also a bunch of huge cables that allow light-speed data travel under the ocean.

Facilitator

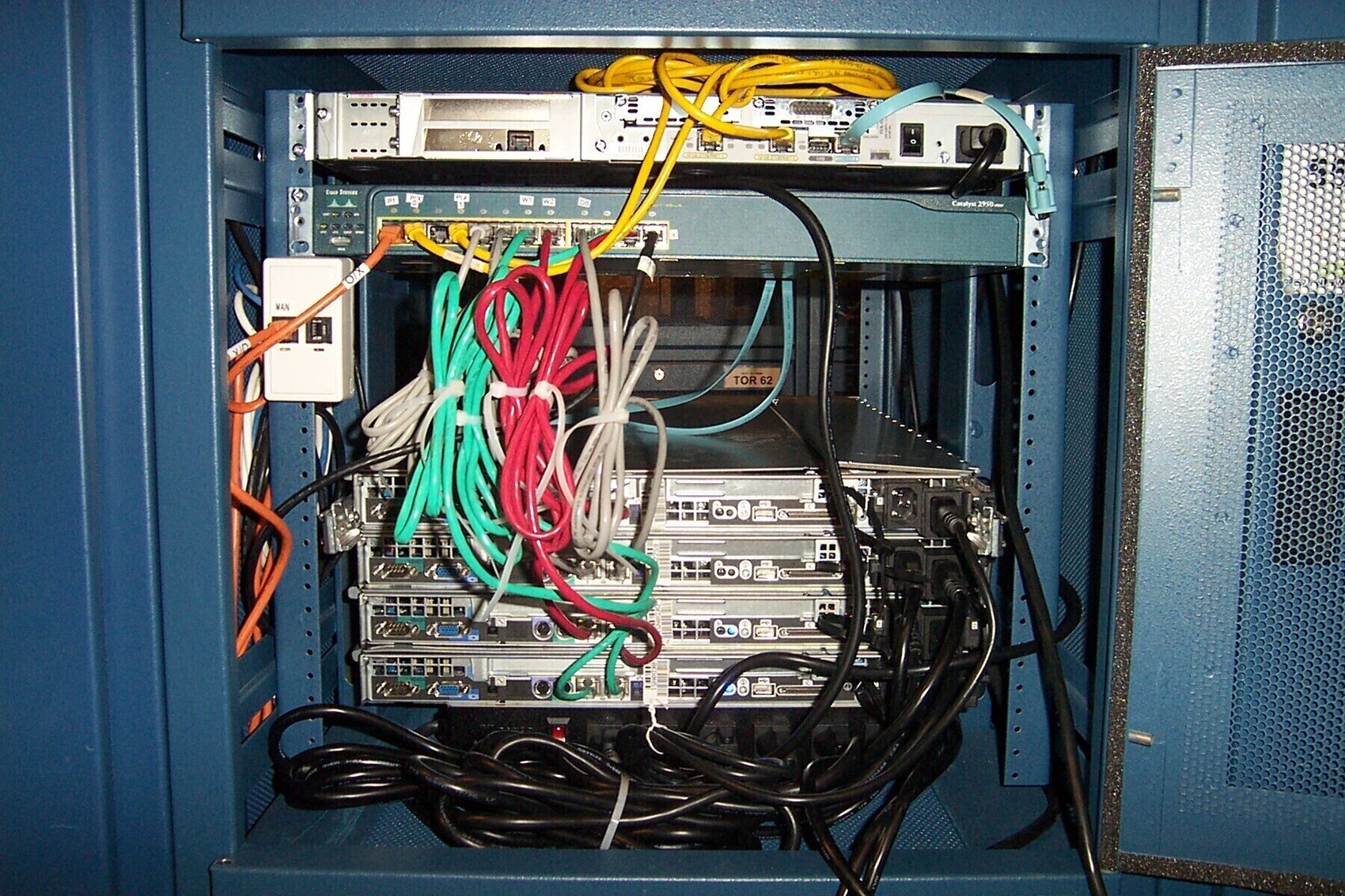

These cables are also in our cities. This is an internet exchange point cabinet in Paris, France. Each cable corresponds to 1 router, probably each in one apartment. Think how many there is just in your street/neighbourhood. Looking like this the internet feels all of a sudden very fragile too.

Facilitator

Internet is also a bunch of satellites and antennas to allow connections everywhere, by all types of devices. This infrastructure is also growing with the rise of wireless devices (autonmous cars, smart CCTV, etc.) Image: 5G antenna in Köln, Germany.

Facilitator

Although Internet looks mostly like the previous images for us in the Global North, it’s not necessarily the same everywhere. In Cuba, Internet is still not always available, heavily censored and low-bandwidth. There are a lot of self-made connections and DIY antennas, like the power meters on the picture above.

Facilitator

All of these data-centers, satellites, antennas, exchange points, phones, laptops and other devices: need to be powered, by real (not virtual) energy. Sometimes it’s wind-turbines like in Agriport (although it monopolizes this green energy source, taking it away from nearby villages). Sometimes, it’s powered by fossil-fuel directly: coal electric plants, etc.In any case: it’s a massive and growing energy consumption footprint. Especially since it’s always ON!

Facilitator

Last but not least, let’s not forget: All those computers, cables, antennas, etc. are made of very physical materials. Materials hard to get, like metals that we extract all over the globe, often in violation to human rights (Like in Congo, see image but also in Chile, Australia, Indonesia) but also with a huge pollution.

Now that we have a better images of the different types of infrastructure that compose the Internet, we ask ourselves: what precisely is a server?

What is a server?

Now that we have seen a bit what the Internet is made of, let’s zoom-in the part we are interested in today: servers

Facilitator

Before we go to the next round of images, around a server, we can do a short round of intervention from participants, with a open question: “We have heard the word “server” in the above presentation, but what do you think is a server, in your own wording?”

Facilitator

Internet is made of computers, with different shapes and functions. Materially: servers are usually computer placed on racks, without screens, connected to other computers with cables. In this image, each “rack” is a server.

Facilitator

Functionally: a server does what its name implies. It serves (sends) informations. In computing we refer to client as the computers that ask to retrieve informations, files or calculations. For example here, a “client” ask (requests) Wikipedia’s server for its front page file, the server responds and send it back.

Facilitator

Essentially,a server is just a computer configured to talk to other computers. It actually doesn’t have to be in a data center, it’s mostly for speed, and energy efficiency reasons. Historically, most companies and universities were running their own servers in their IT department, hosting their own software. They also had an intranet for handling their professional files (a local network).

Facilitator

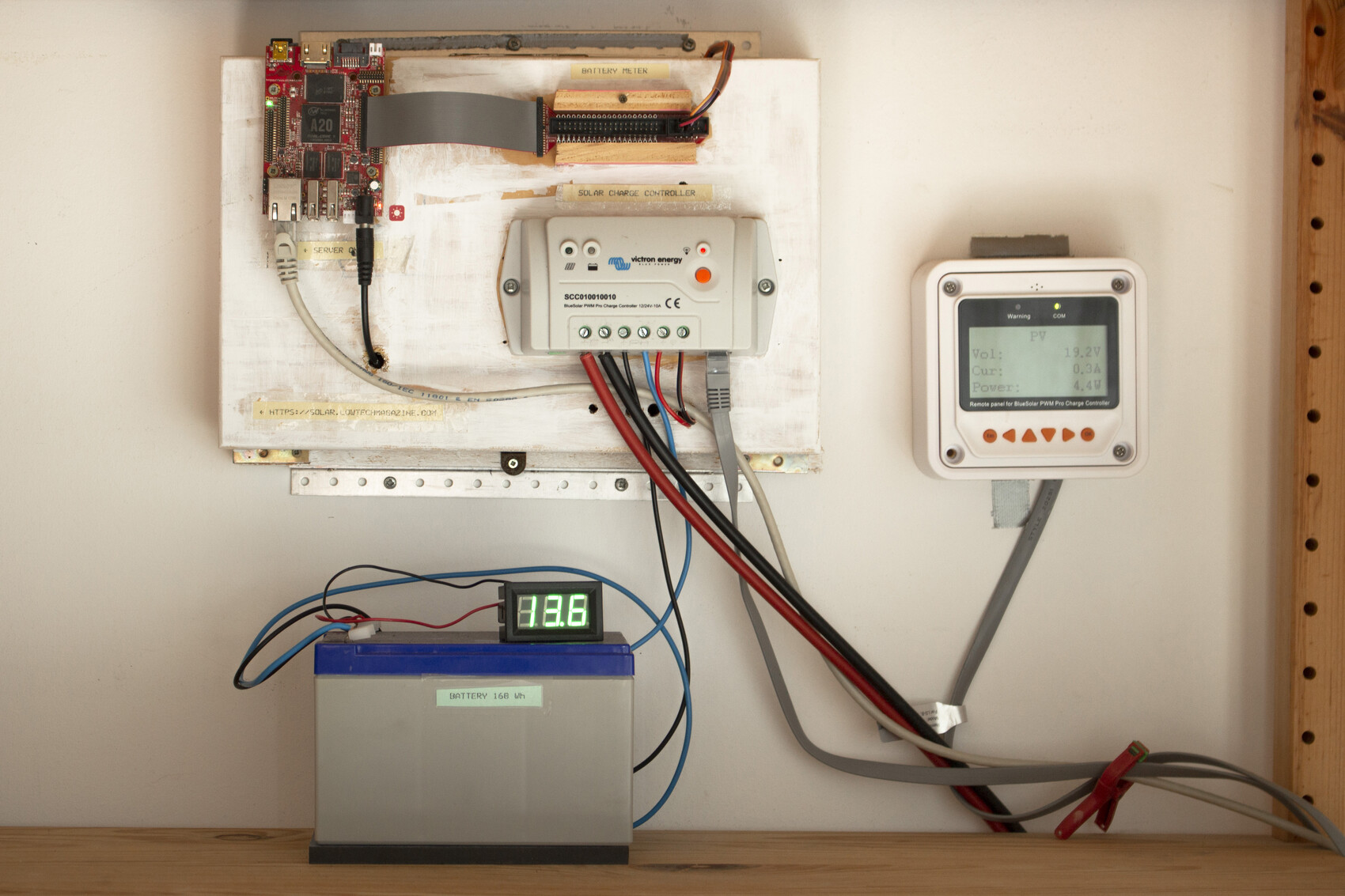

Some people actually have their own server at home. Like Club1.fr in the image. This Paris-based association hosts websites for artists in a server at one of the member’s place, in a cupboard. Here they are setting-it up in the living room. This is called self-hosting.

Facilitator

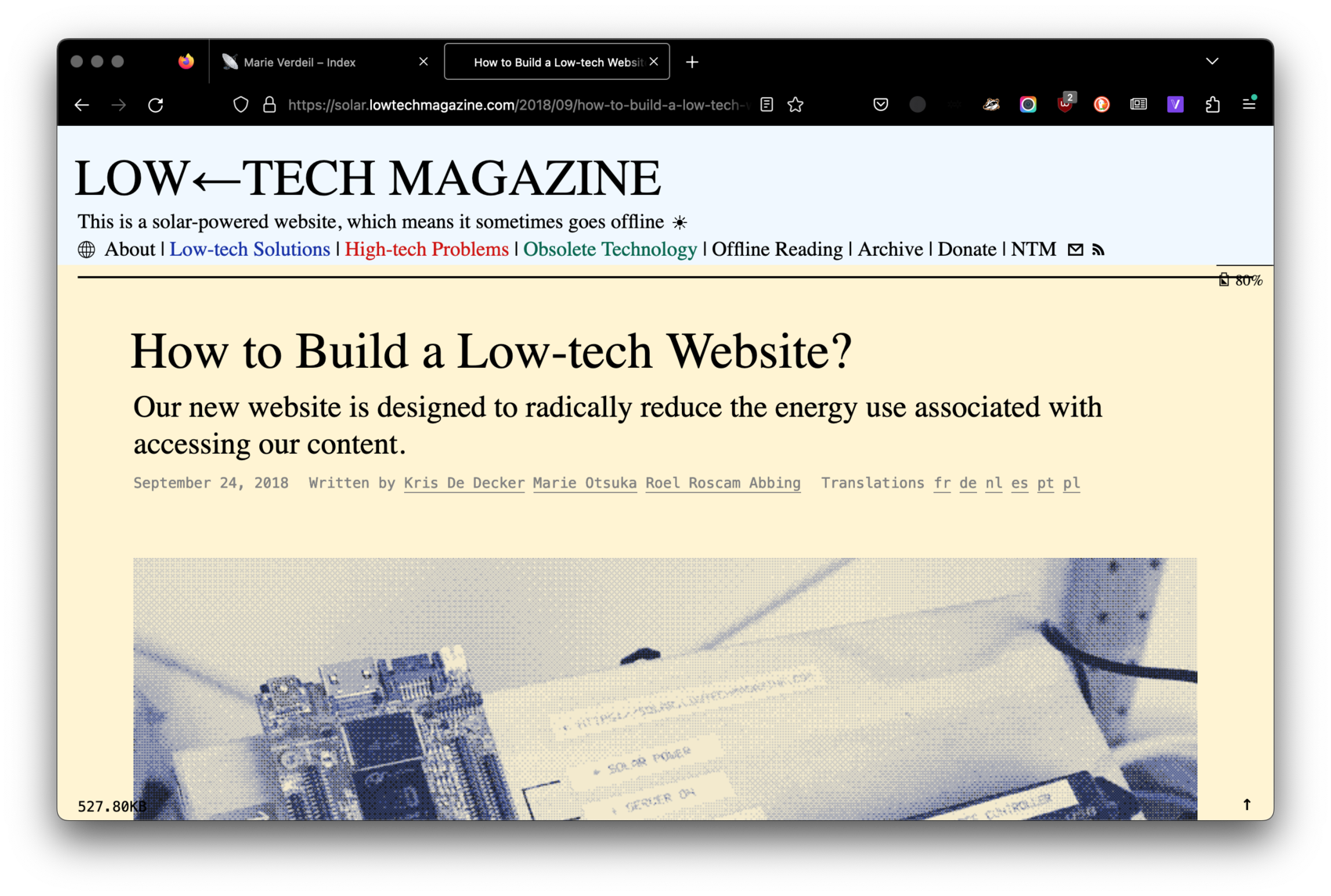

Self-hosting server is way to get more control on your data (privacy reasons), but also more control on the infrastructure. This is the server and infrastructures that powers the website of Low-tech Magazine, a techno-critical online media.

Facilitator

The server runs on a tiny 2W computer, powered by a single solar panel. When the weather is too bad, they chose to let it run out of battery and turn off, rather than having spare batteries and backup oil generators, like data centers have. 100% uptime also has a cost, and a pricy one.

Facilitator

Consequently the website hosted is highly compressed, to fit on this tiny device and serve content as lightweight as possible. No videos, no tracking, dithered images.

Facilitator

Can we do something similar to have host text and images ourselves? Yes with our phones: essentially a free, powerful, battery optimised computer. This is what we will do now!

Talking “server” to my phone : the terminal

To be able to turn our phone into a server (that is a computer that can send back information when asked to), we have to install a couple apps on there.

The main app is called Termux. You can access its technical documentation on this wiki. Termux is an terminal emulator and package collection. The app enables us to give direct commands to the computer (or phone) and download other software (piece of code packaged in folders).

Facilitator

In this part, we explain what a command-line interface (terminal) is and we download Termux.

WTF is a Terminal?

Facilitator

This theorical part (below) can be done in parallel of downloading Termux (see next step). For example, while we wait for the APK (install file) to download. In that case, maybe going faster and skip some images.

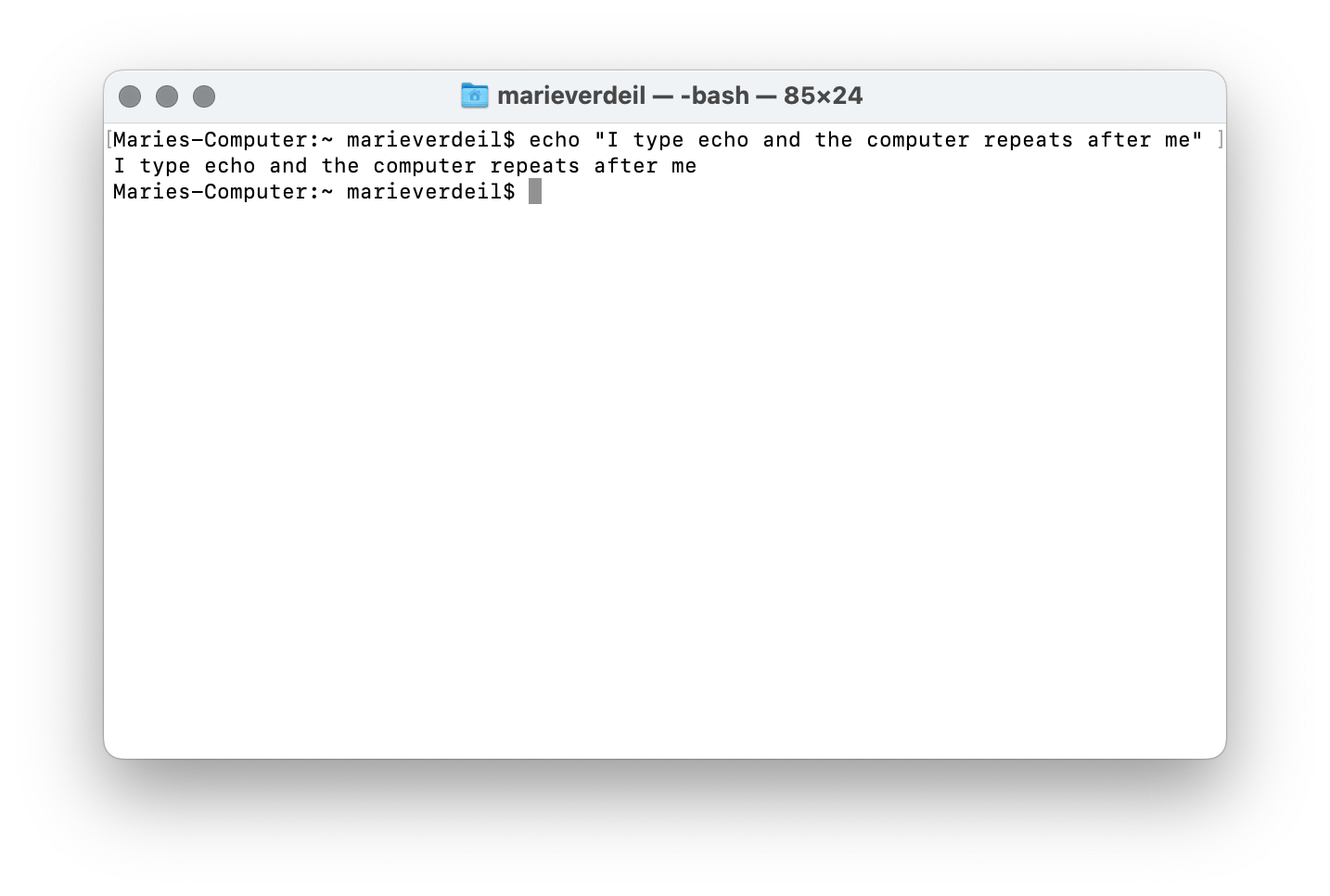

Before we just into the instructions for downloading Termux, let’s take some time to understand what we are doing. As we said, Termux is a terminal emulator but what is even a Terminal?

A CLI, Command Line Interface, also known as a terminal is an walk to communicate to the computer using text, instead of buttons or voice. It goes like this:

- A user types a line of command with his keyboard and presses enter

- The computer answers with an other line corresponding to the command: executing a task, providing information, downloading a package (pkg)

For example:

pkg update

...

[Installing package......99%]

Package successfully updated.

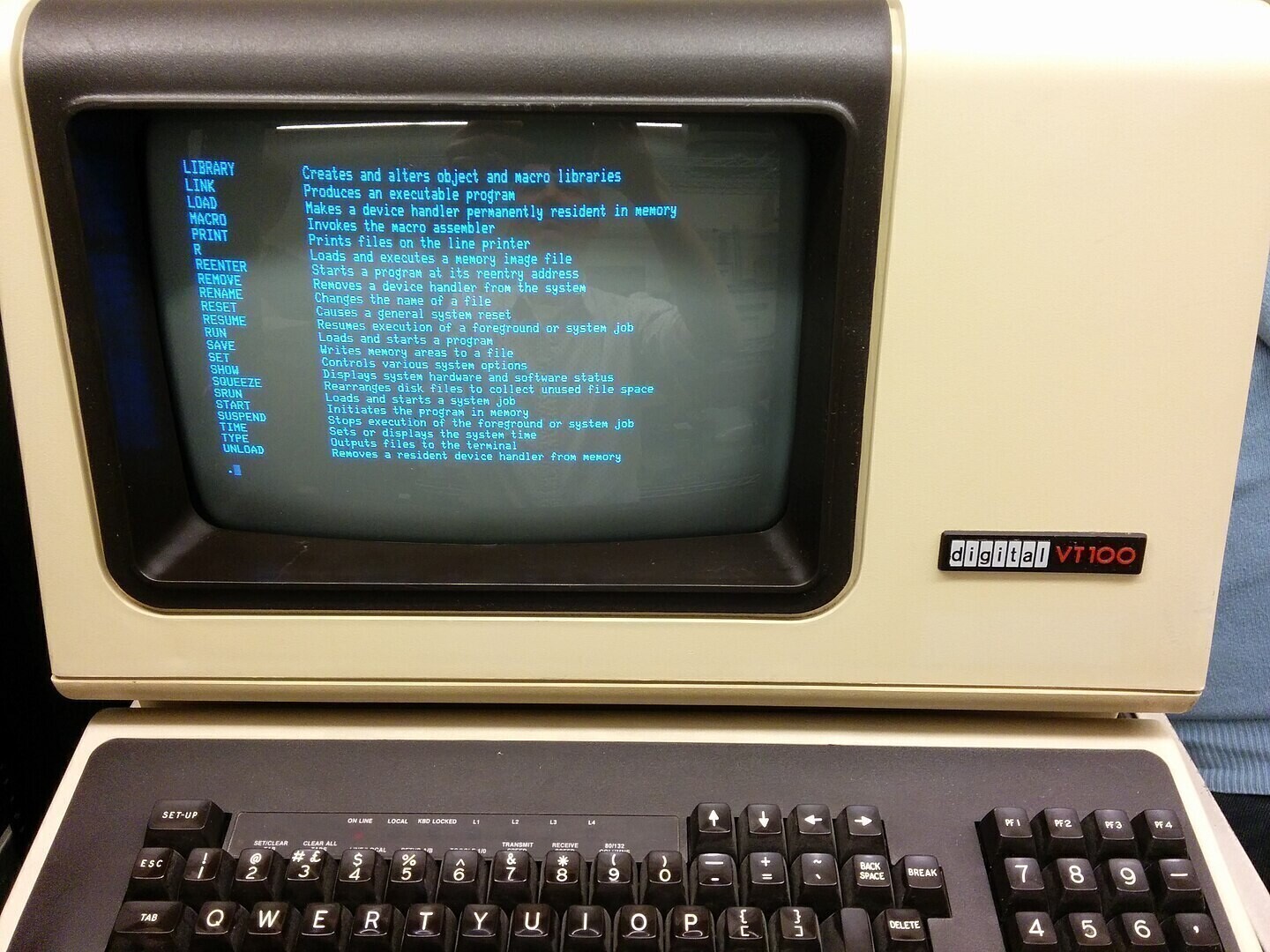

Every computer can be accessed via the CLI instead of the more familiar GUI, the Graphical User Interface that we are used to, with buttons, images, a mouse, a touch-screen, etc. On Linux and MacOS we can use the default Terminal app, on Windows there is _Windows Powershell or PUTTY.

The command line is also how we communicate with computers that don’t have a screen and/or are far away, like servers!

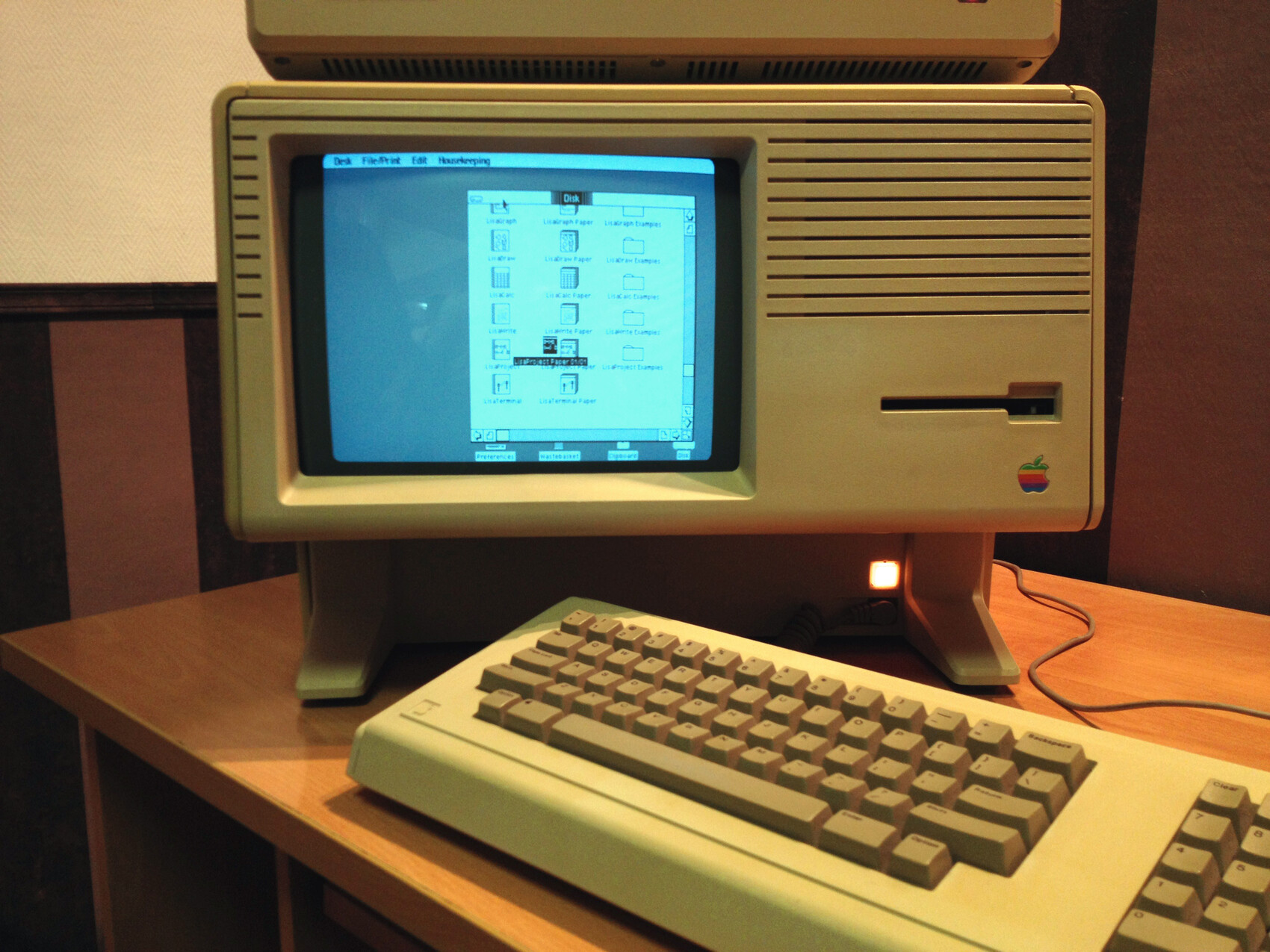

Before the democratisation of home computers and the subsequent invention of the Graphical Interface, all tasks performed on the computer were executed through text command. Actually clicking on buttons, menus and folders is just a “user-friendly’ layer hiding what is really going on. Every “click / tap” triggers a command, or a series of commands to the computer too, we just don’t see the text anymore.

Termux is also a command-line interface but for Android phones. Because we are trying to turn our phone into a server, which is not its main function, we have to do it directly by typing command in a Terminal window, which is why we install Termux.