How to Print?

To print this page or save it as a PDF, press CTRL + P or File > Print > Destination > Save as PDF

Composting Mobile Phones - Hosting server on obsolete mobile phones

Exposing the Cloud, its servers and their energy footprint through everyday devices

What is this workshop about?

In this workshop we collectively examine the infrastructure behind the Internet by building a our own (prototype) server on an old smartphone.

Since the democratisation of the Internet in the 90s, the operations and communications we perform on the Internet have kept rising massively. Nowadays, we often hear about the cloud, as a way to describe all the online services that we access daily, such as emails, social media, data storage, video-streaming, AI chat bots, etc. But what does the Internet look like behind this fog screen?

Although it might seem light and airy, the Internet’s virtual world is actually made of tangible infrastructures with a rising ecological footprint.

The mobile phone as an entry point

This investigation into the materiality of the internet starts by the most intimate and familiar object: the smartphone. This device is also our “window” to the internet since it is so dependant on the so-called “cloud”: our modern phone’s power lies in all the servers it’s accessing remotely. Nowadays it sometimes feels like a phone without an online connection isn’t much use. However, a smartphone is also an highly optimised, low-power computer——a device capable of computation——just in a different form factor than that of a laptop or a rack server. Actually tablets, a smart vacuum cleaners, and even some e-cigarettes are also computers etc.

Although planned obsolescence pushes us to replace our devices every few years, those “retired” smartphones and tablets still hold a lot of computing potential. Because a smartphone’s embodied energy is so high (the energy used for its construction), it’s essential to think about giving them a second-life, which is exactly what we do in this workshop.

Let’s begin !

Guide structure

The guide is structured in 5 main parts:

- Before we start (what is needed)

- What is a server? (image presentation about the materiality of The Internet)

- Talking “server” to phone (short theorical intr to terminal and install Termux)

- My phone as a webserver

- Going online

Do you want to follow this tutorial online?

In this case, click on the button below to start or skip the theory directly to the step-by-step instructions by clicking here

Are you a workshop participant?

In this case, you can follow online or download and print a hand-out version:

- visit the Participant Hand-out Page

- press

ctrl + PorFile (browser ) > print > destination > Save to PDFto download and print the PDF.

Are you planning and/or facilitating this workshop?

- Head to our workshop preparation section to read some advice before preparing.

- In the Facilitator Guide section , find annotated versions of the Presentation (theory part) and tutorial part (hands-on part)

- You can also download and print the Facilitator Hand-out (simply press

File (browser )> print > destination > Save to PDFto download and print the PDF).

Before we start — What do we need?

We need… A smartphone

This tutorial is made for Android smartphones and tablets from the last 10 years (2015-2025). In case your phone is older than 10 years, not an Android phone, or you are working with a laptop, look below at the alternatives.

You can use your daily phone or an older “retired” device. It can be a bit damaged but the following features are necessary:

- Android 5 or above (Android 7 or above is preferable) (check in Settings > About Phone)

- The Wi-Fi functions.

- The charging port works.

Optional but better:

- The touch screen works, even though it could be shattered. If you don’t have a working screen, check out these solutions.

- The battery functions, or you have an external battery.

Alternatives

iPhones and iPads

Termux — the app we use in this tutorial — is not available on iOS but there is an alternative app called iSH available on iOS 11 and +. Some web-server tutorials are available online (using iSH and python web-server).

PostMarketOS

If your Android phone is simply too old, cannot update or you are looking for a different (radical) approach, check out PostMarketOS.

PostMarketOS is an alternative Linux OS that is free, open-source and community maintained. You can install it as a replacement for Android and extends your phone’s lifespan beyond its programmed software obsolescence (lack of updates). You can then easily install the web-server software of your choice, following a linux web-server tutorial.

more info will be added here.

Laptops

If you don’t have a spare phone but a spare laptop, you can install Linux on it and deploy a web-server too. Simply look for “installing nginx on Linux” tutorial.

Factory Reset your phone + Google’s FRP (optional)

This step is optional, but it might be handy to clean up your phone before deploying it as a web-server. It will give you more storage space, and prevent other apps to overtake computing power.

To do this, online search your device model + factory reset. You will find some instructions to access the boot mode of your computer, from which you can select wipe phone or factory reset. A good website is Hard Reset.

Before you reset your phone:

- Back-up the the contents your want to save, it will be erased.

- Make sure to disconnect any Google Account in Settings > Accounts. Otherwise you risk facing Google’s FRP protection prompting you to login again to the previous Google account, which would make your phone (almost) unusable. This makes it harder to start with a phone you bought or got from someone else.

Smartphone set-up

Make sure your phone is:

- Accessible (you have the password)

- Connected with the internet on a Wi-Fi network

- Equipped with a web-browser (for example, Mozilla Firefox or Chromium).

The (real) shape of the Internet

Facilitator

Depending on the drawing outcomes and the knowledge level of participants, the presentation might need to be adapted (sharing more or less information).

The following image series gives an introduction to what the internet really looks like, beyond the usual diagrams and icons we often see.

Facilitator

If the internet feels hard to understand, that’s because it’s mostly hidden. Hidden because it’s on purpose, not just because it’s complicated. First, because everyone has been telling us that the internet is “immaterial”, “virtual”, “remote”. Exactly like when we search online: clouds, airy drawing, graphs, etc.

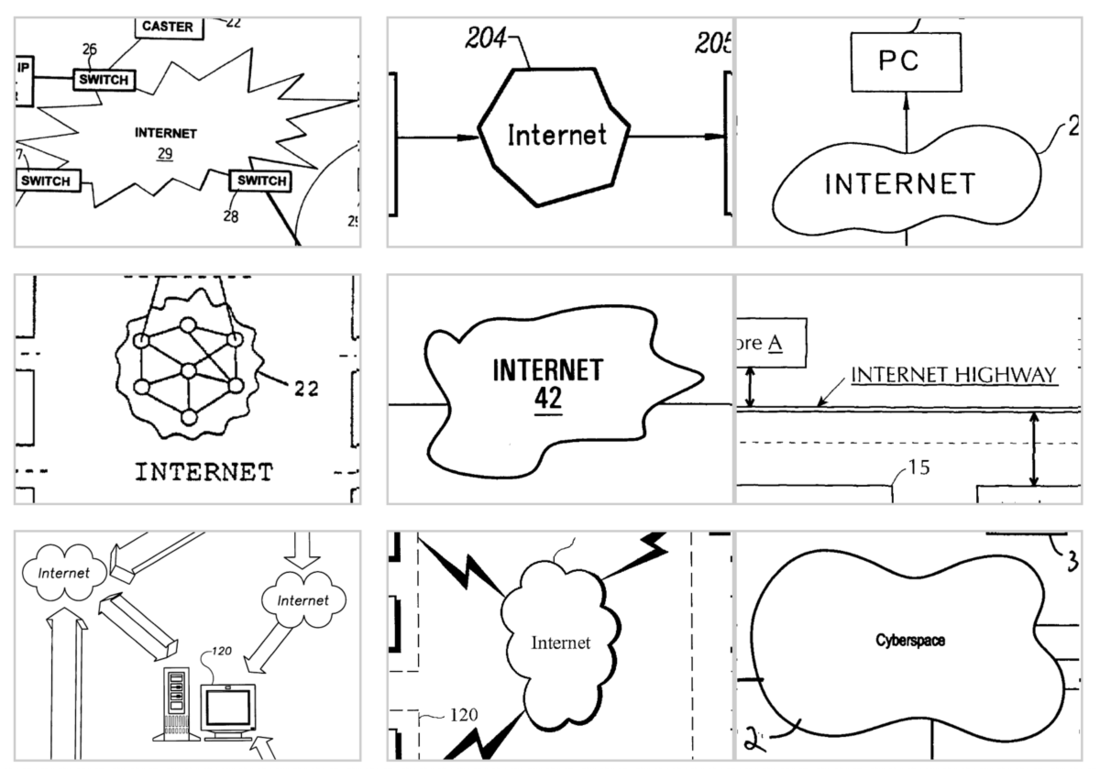

Facilitator

An artist called Noah Veltman summarizes this very well in this drawing collection: the Internet is apparently a “bean” or a “cloud”. But although the internet is a network (that part is true), it definitely is not “light” or “clean”, but rather it’s heavy and dirty. Let’s see why.

Facilitator

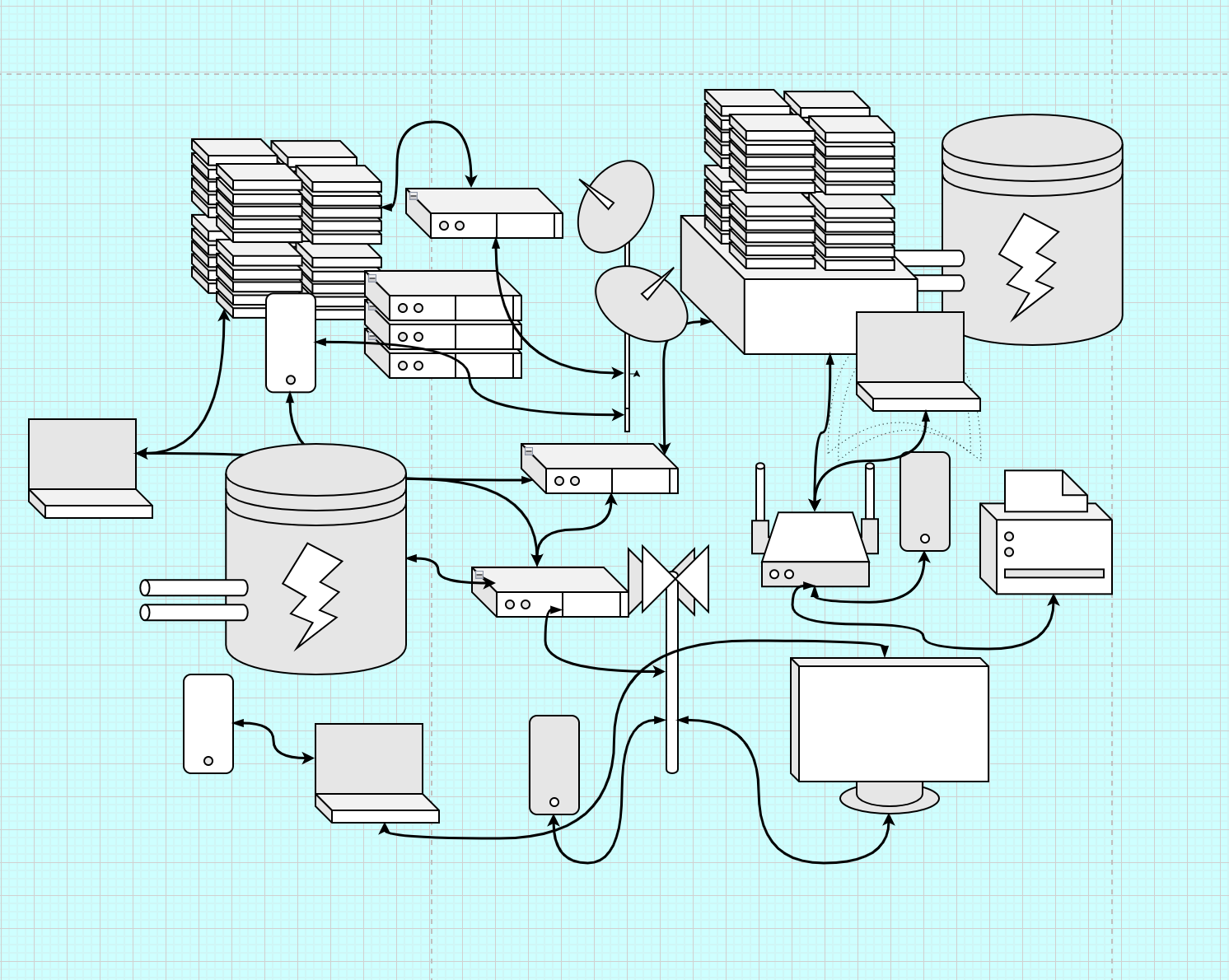

What the web really looks like: A/ Abstractly—like an this illustration— it’s a network of computer networks. Different types of computers: 1-Servers, to serve contents 2-Clients: computers retrieving content (phones, laptops, game consoles, TVs, but also bankcard machines, smart fridge, surveillance cameras, road radars, etc.)3-DNS (aka Domain name servers): to point clients to servers, but also switches, exchange points, etc. 4-All the infrastructures that supports those connections: power plants cables, antennas, etc.

Facilitator

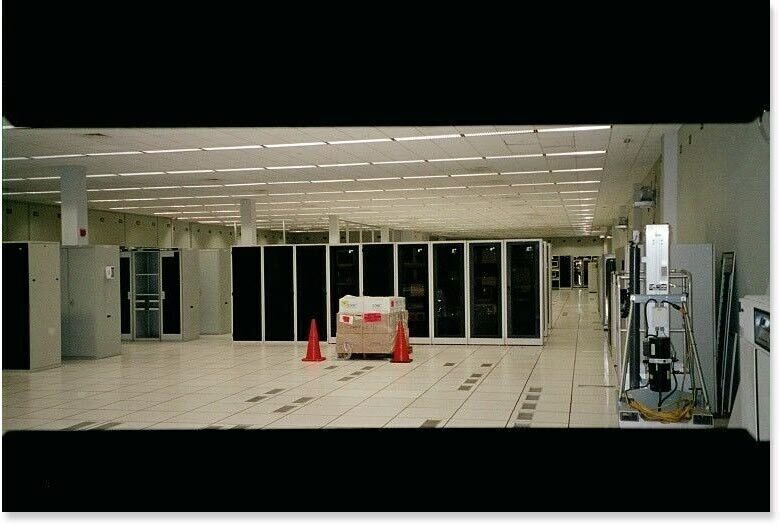

All of this infrastructures: it’s very tangible, and it’s around us. Most of these computers/servers : they live in data centers. Datacenters are buildings housing computers, equipped with cooling systems, energy systems, etc.

Facilitator

These data centers: not only in the US. Everywhere and more and more, especially since AI is becoming so important. Image above is from the Datacenter cluster north of Amsterdam, in Agriport. Neighbors to industrial farms, producing tomatoes and peppers all year long. Datacenters are as big and impactful as any other factory.

Facilitator

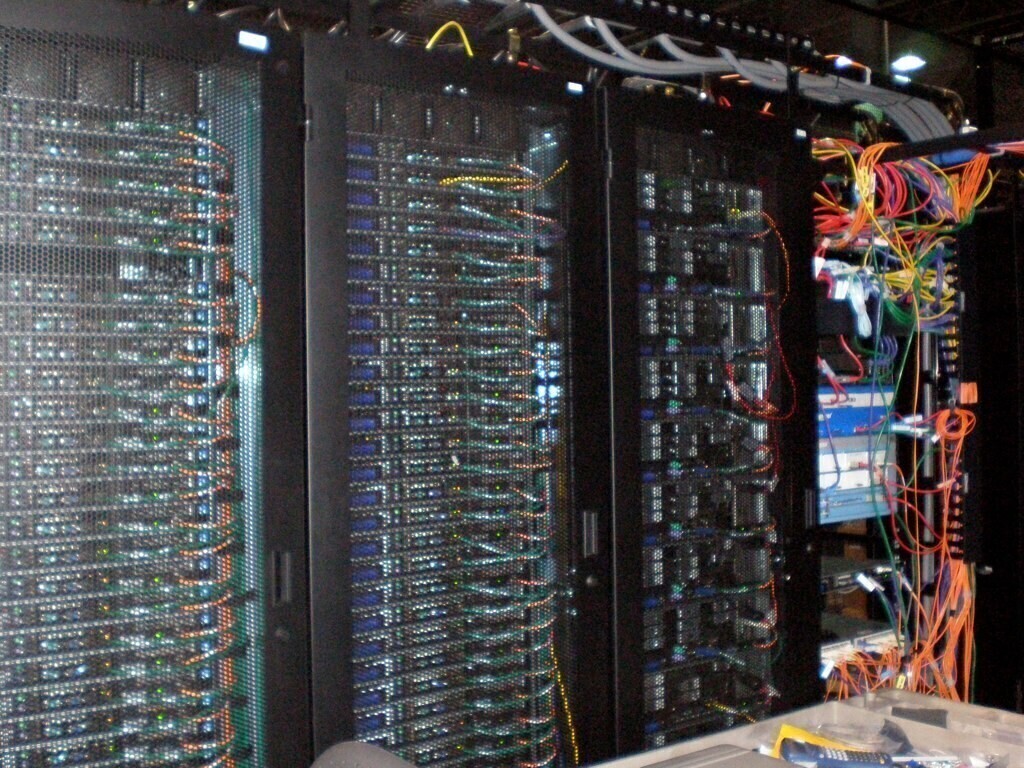

Inside: looks like that: rack servers (shelves full of computers), all connected together to add up their power/speed. Those computational processes produce a lot of heat.

Facilitator

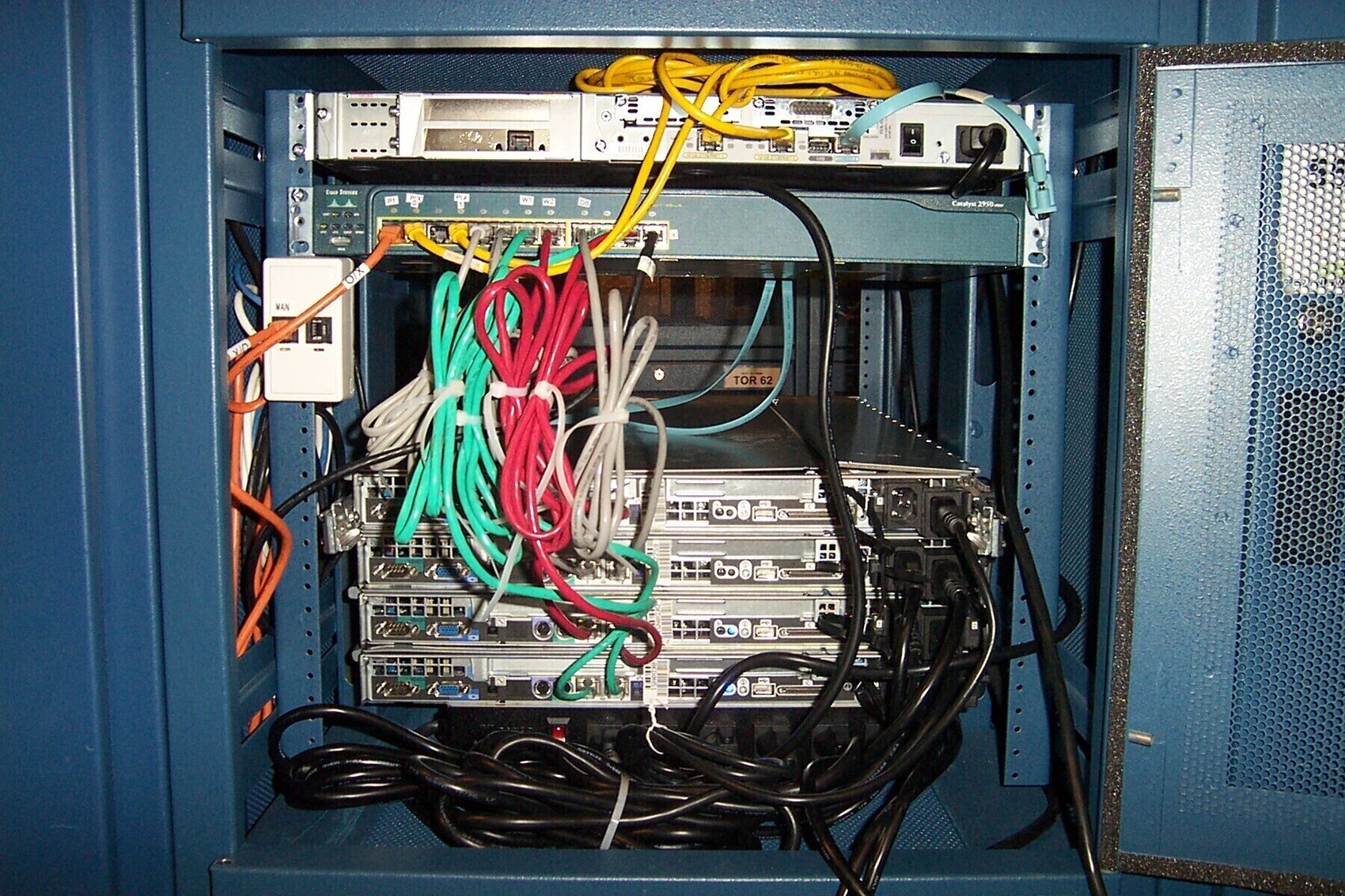

All these computers in datacenters need to be connected to our devices at home/office. Internet is also a bunch of huge cables that allow light-speed data travel under the ocean.

Facilitator

These cables are also in our cities. This is an internet exchange point cabinet in Paris, France. Each cable corresponds to 1 router, probably each in one apartment. Think how many there is just in your street/neighbourhood. Looking like this the internet feels all of a sudden very fragile too.

Facilitator

Internet is also a bunch of satellites and antennas to allow connections everywhere, by all types of devices. This infrastructure is also growing with the rise of wireless devices (autonmous cars, smart CCTV, etc.) Image: 5G antenna in Köln, Germany.

Facilitator

Although Internet looks mostly like the previous images for us in the Global North, it’s not necessarily the same everywhere. In Cuba, Internet is still not always available, heavily censored and low-bandwidth. There are a lot of self-made connections and DIY antennas, like the power meters on the picture above.

Facilitator

All of these data-centers, satellites, antennas, exchange points, phones, laptops and other devices: need to be powered, by real (not virtual) energy. Sometimes it’s wind-turbines like in Agriport (although it monopolizes this green energy source, taking it away from nearby villages). Sometimes, it’s powered by fossil-fuel directly: coal electric plants, etc.In any case: it’s a massive and growing energy consumption footprint. Especially since it’s always ON!

Facilitator

Last but not least, let’s not forget: All those computers, cables, antennas, etc. are made of very physical materials. Materials hard to get, like metals that we extract all over the globe, often in violation to human rights (Like in Congo, see image but also in Chile, Australia, Indonesia) but also with a huge pollution.

Now that we have a better images of the different types of infrastructure that compose the Internet, we ask ourselves: what precisely is a server?

What is a server?

Now that we have seen a bit what the Internet is made of, let’s zoom-in the part we are interested in today: servers

Facilitator

Before we go to the next round of images, around a server, we can do a short round of intervention from participants, with a open question: “We have heard the word “server” in the above presentation, but what do you think is a server, in your own wording?”

Facilitator

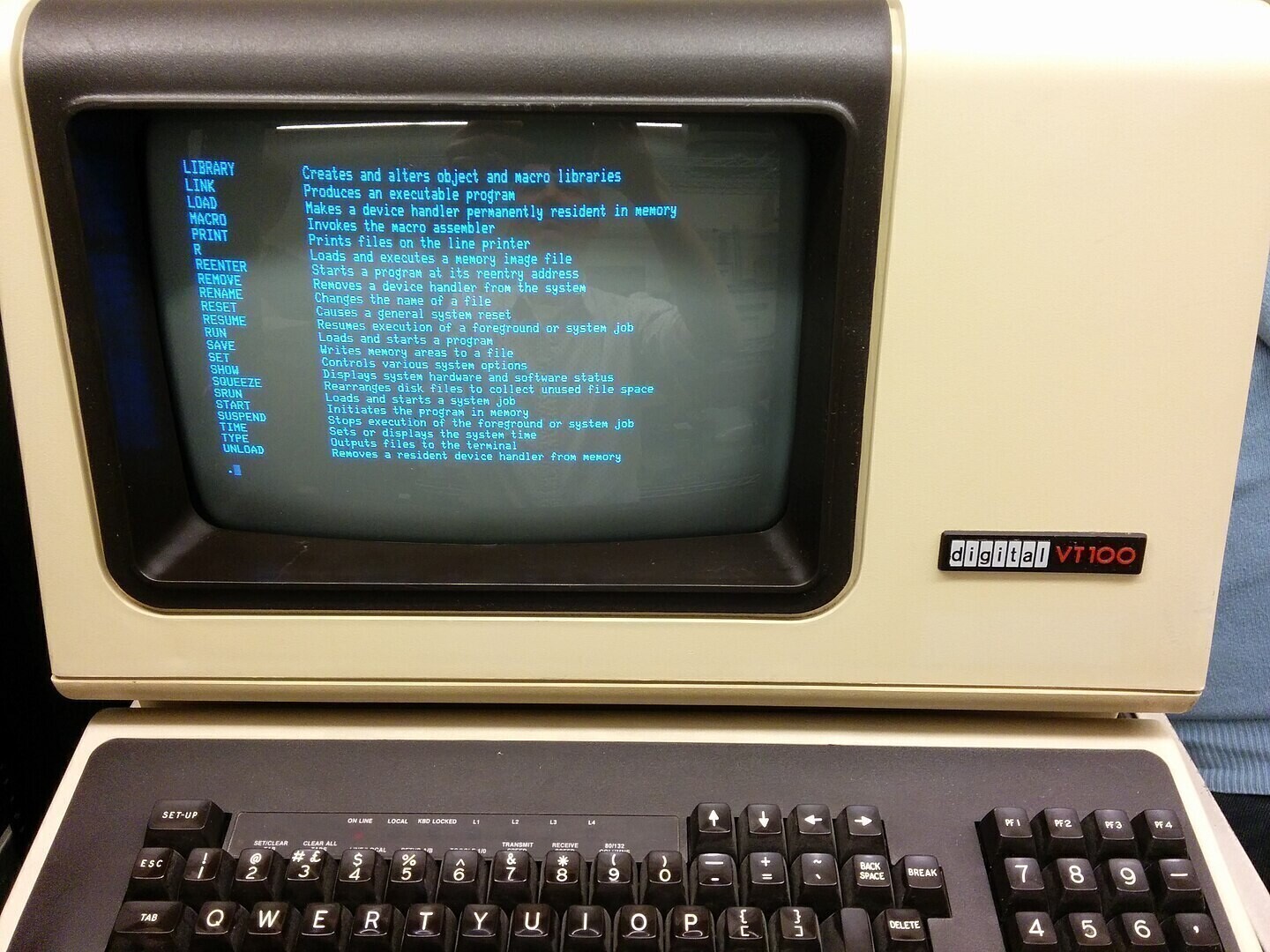

Internet is made of computers, with different shapes and functions. Materially: servers are usually computer placed on racks, without screens, connected to other computers with cables. In this image, each “rack” is a server.

Facilitator

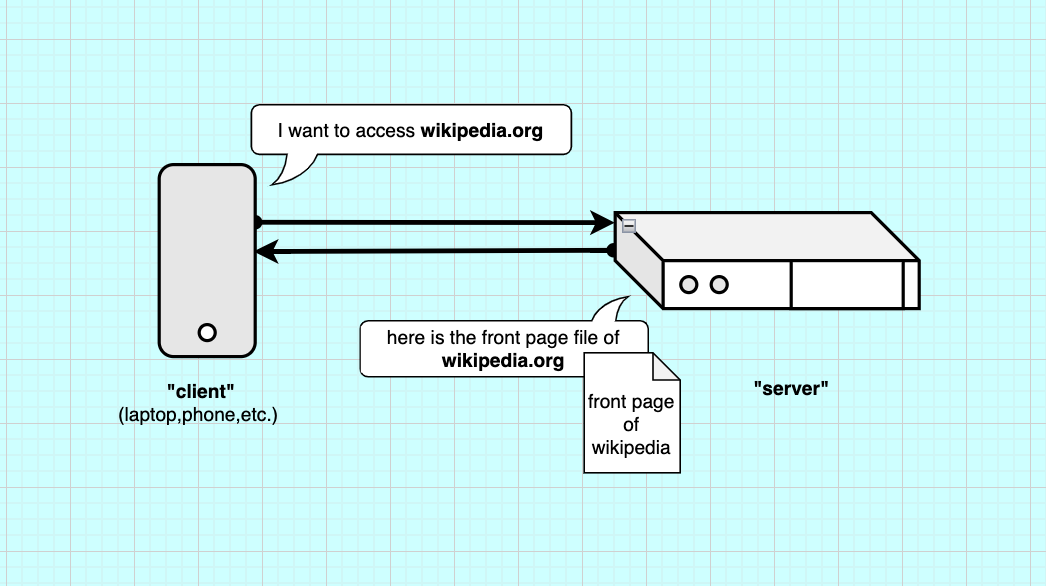

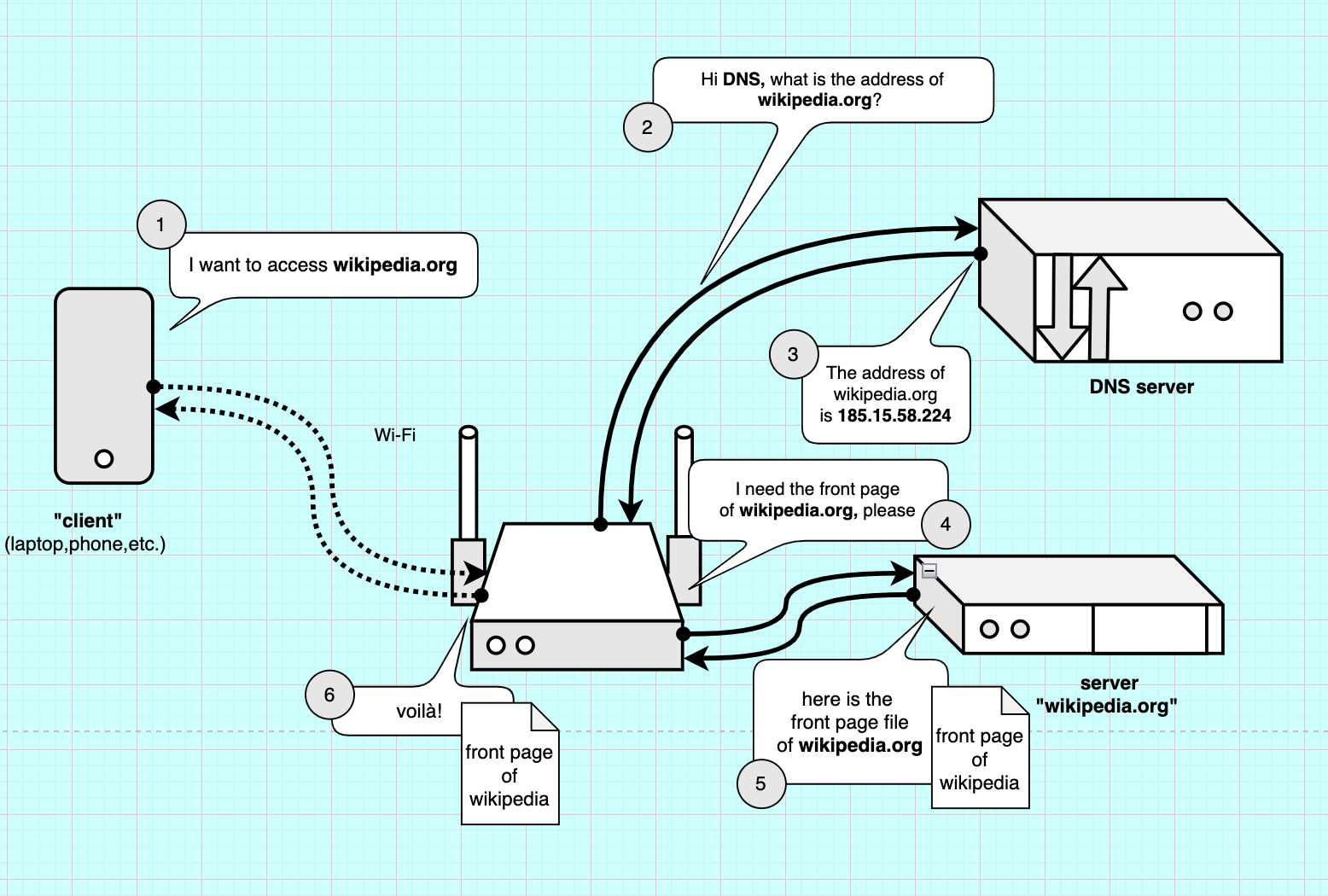

Functionally: a server does what its name implies. It serves (sends) informations. In computing we refer to client as the computers that ask to retrieve informations, files or calculations. For example here, a “client” ask (requests) Wikipedia’s server for its front page file, the server responds and send it back.

Facilitator

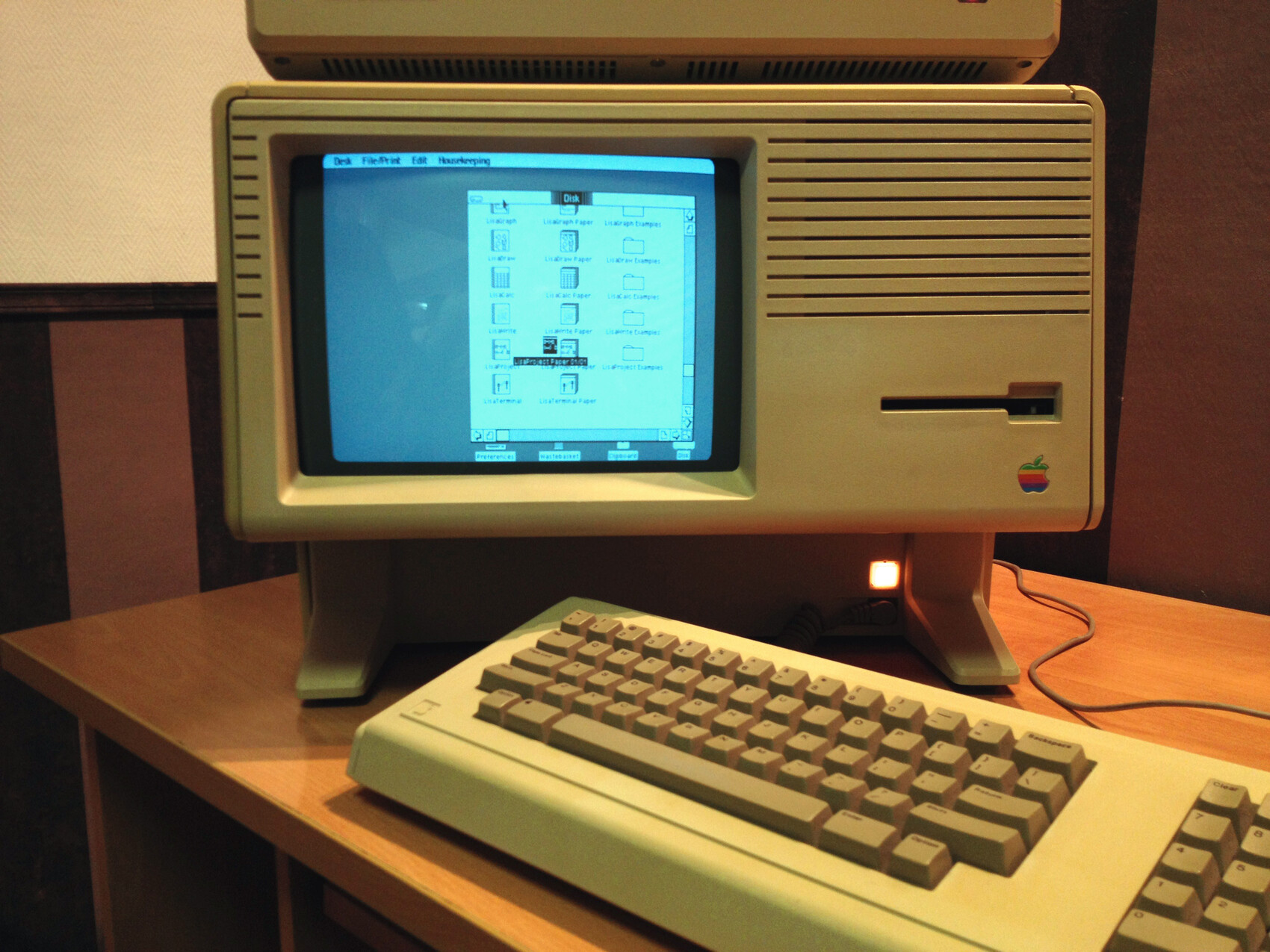

Essentially,a server is just a computer configured to talk to other computers. It actually doesn’t have to be in a data center, it’s mostly for speed, and energy efficiency reasons. Historically, most companies and universities were running their own servers in their IT department, hosting their own software. They also had an intranet for handling their professional files (a local network).

Facilitator

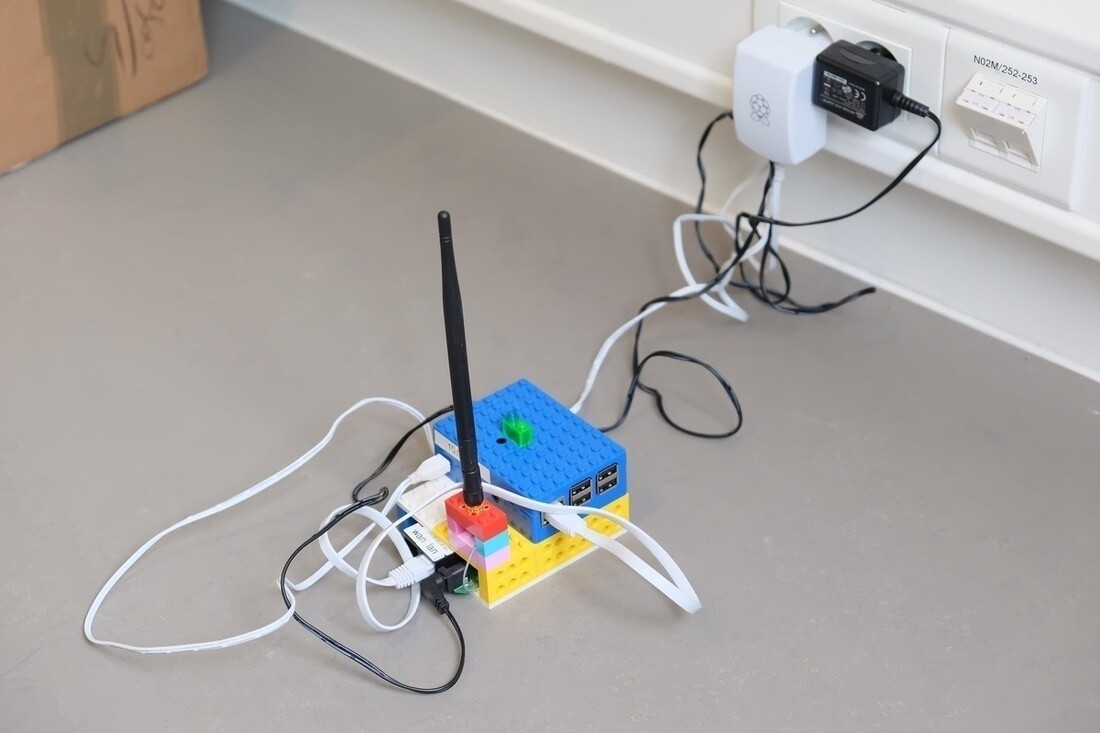

Some people actually have their own server at home. Like Club1.fr in the image. This Paris-based association hosts websites for artists in a server at one of the member’s place, in a cupboard. Here they are setting-it up in the living room. This is called self-hosting.

Facilitator

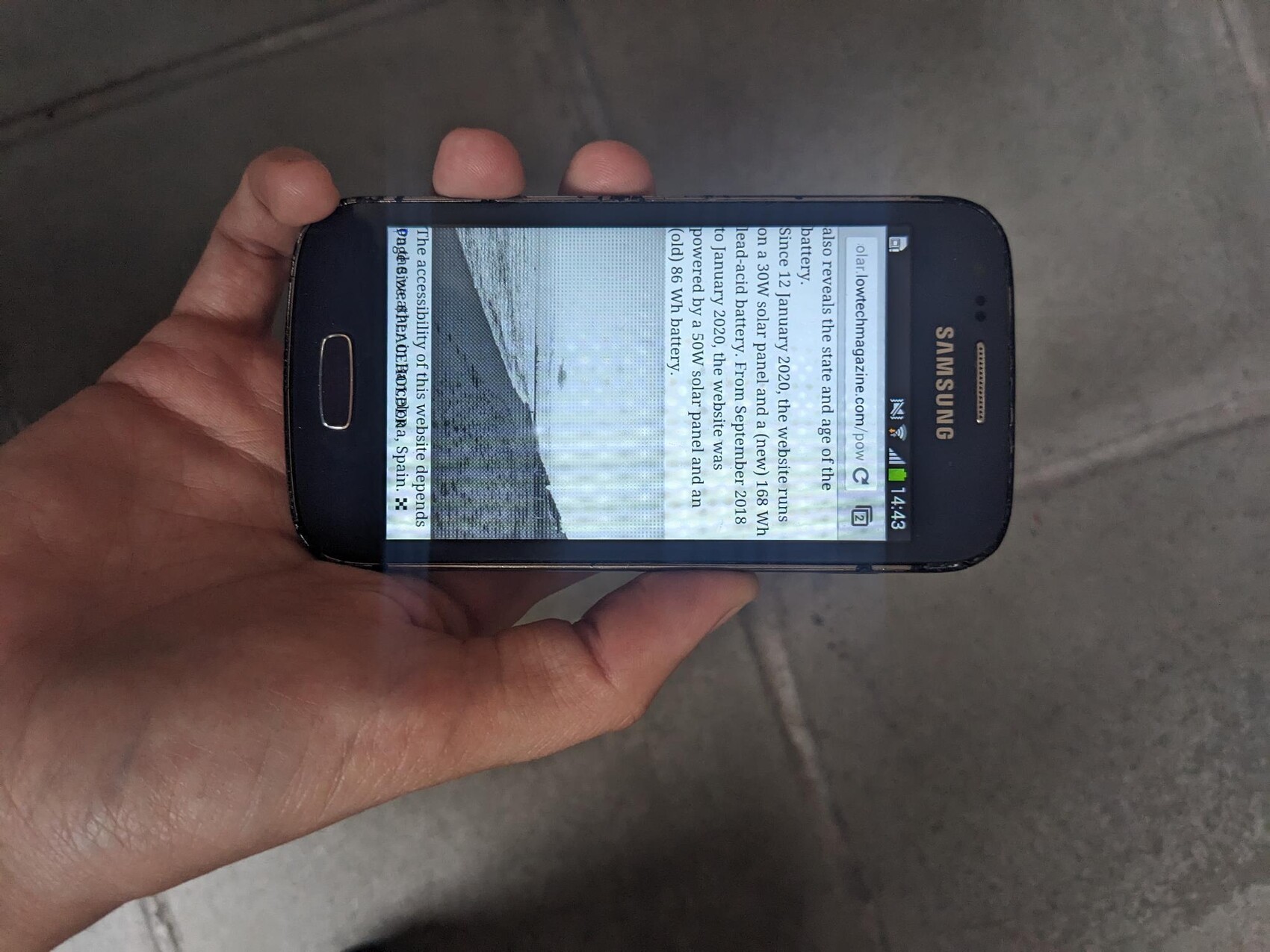

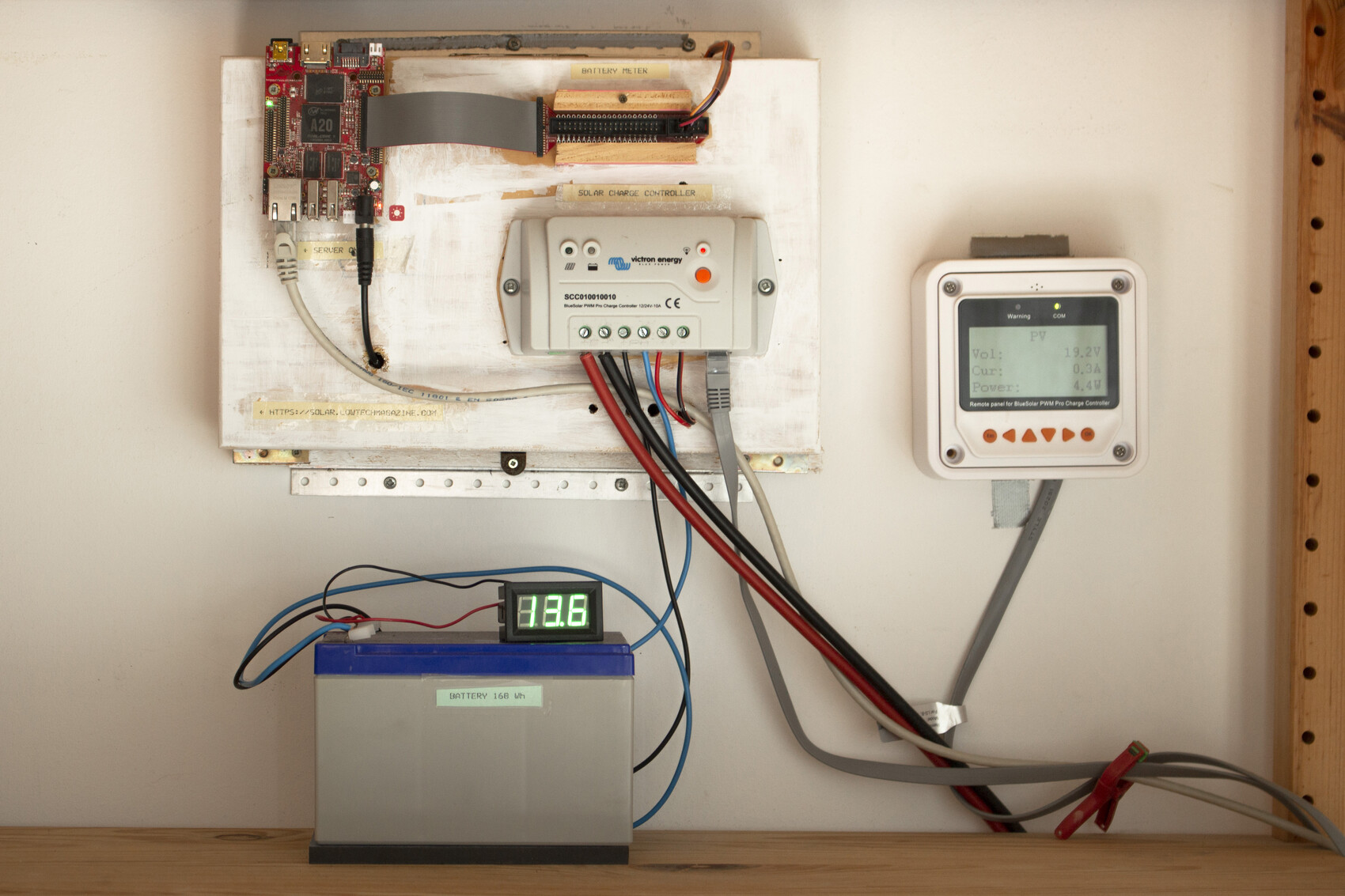

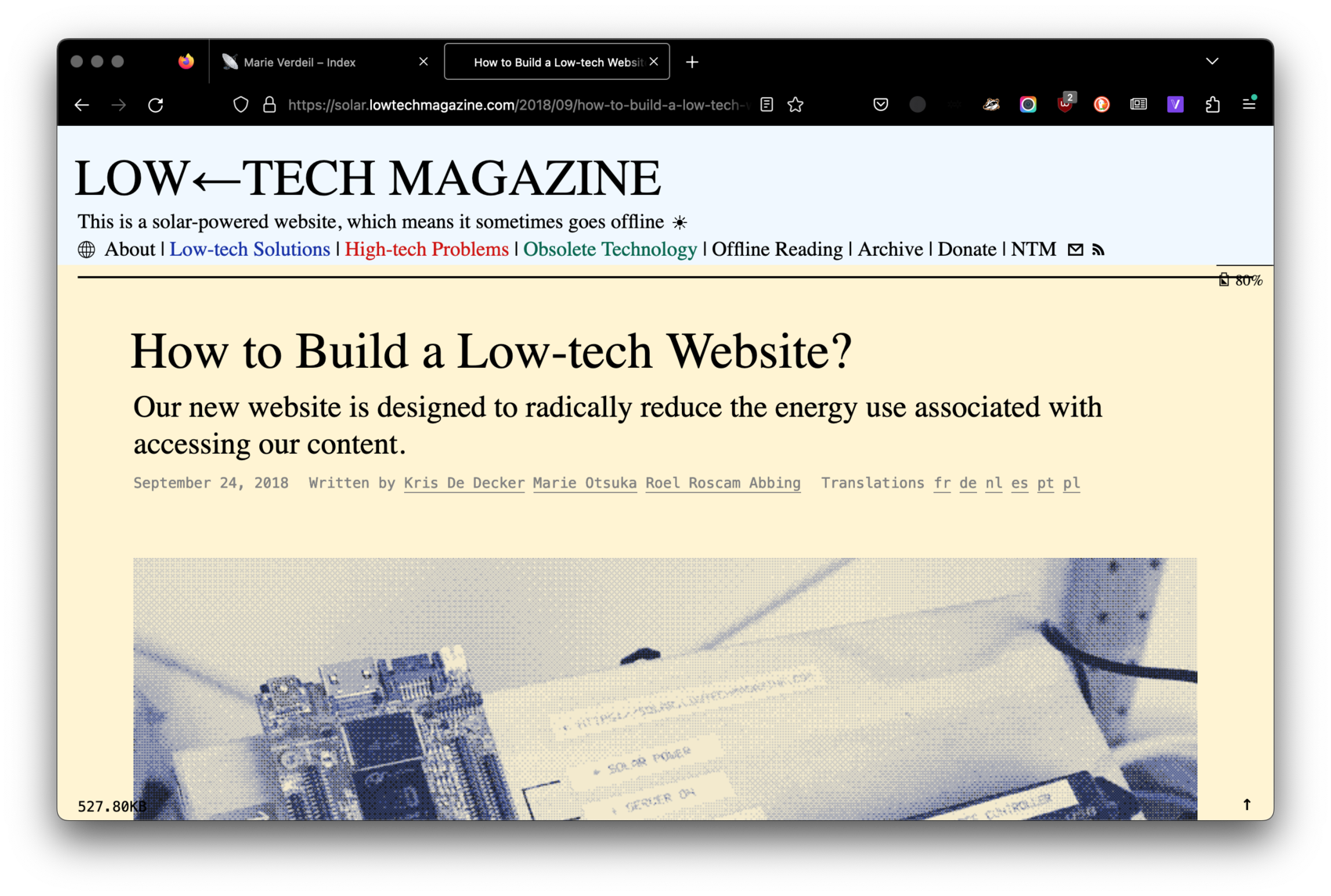

Self-hosting server is way to get more control on your data (privacy reasons), but also more control on the infrastructure. This is the server and infrastructures that powers the website of Low-tech Magazine, a techno-critical online media.

Facilitator

The server runs on a tiny 2W computer, powered by a single solar panel. When the weather is too bad, they chose to let it run out of battery and turn off, rather than having spare batteries and backup oil generators, like data centers have. 100% uptime also has a cost, and a pricy one.

Facilitator

Consequently the website hosted is highly compressed, to fit on this tiny device and serve content as lightweight as possible. No videos, no tracking, dithered images.

Facilitator

Can we do something similar to have host text and images ourselves? Yes with our phones: essentially a free, powerful, battery optimised computer. This is what we will do now!

Talking “server” to my phone : the terminal

To be able to turn our phone into a server (that is a computer that can send back information when asked to), we have to install a couple apps on there.

The main app is called Termux. You can access its technical documentation on this wiki. Termux is an terminal emulator and package collection. The app enables us to give direct commands to the computer (or phone) and download other software (piece of code packaged in folders).

Facilitator

In this part, we explain what a command-line interface (terminal) is and we download Termux.

WTF is a Terminal?

Facilitator

This theorical part (below) can be done in parallel of downloading Termux (see next step). For example, while we wait for the APK (install file) to download. In that case, maybe going faster and skip some images.

Before we just into the instructions for downloading Termux, let’s take some time to understand what we are doing. As we said, Termux is a terminal emulator but what is even a Terminal?

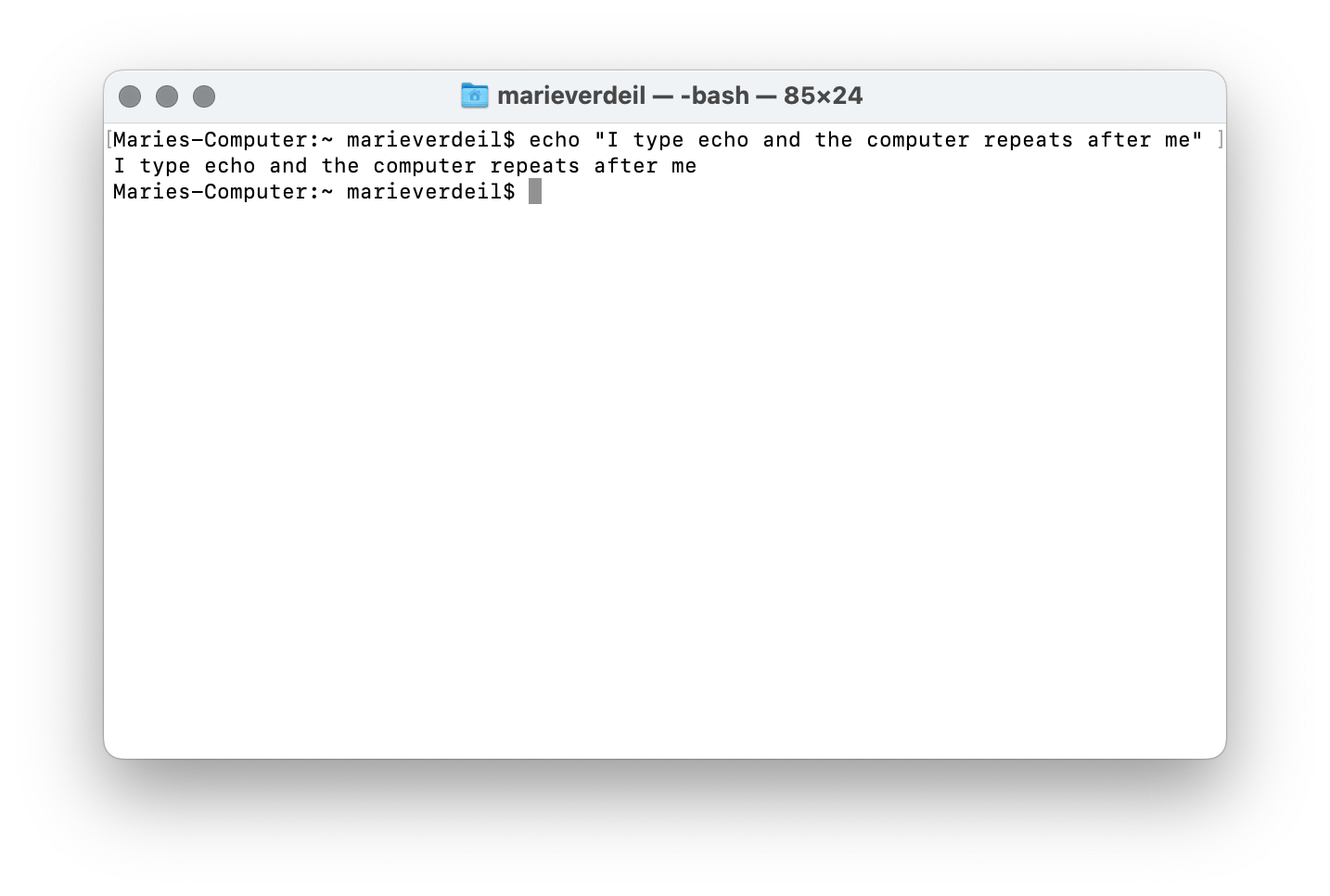

A CLI, Command Line Interface, also known as a terminal is an walk to communicate to the computer using text, instead of buttons or voice. It goes like this:

- A user types a line of command with his keyboard and presses enter

- The computer answers with an other line corresponding to the command: executing a task, providing information, downloading a package (pkg)

For example:

pkg update

...

[Installing package......99%]

Package successfully updated.

Every computer can be accessed via the CLI instead of the more familiar GUI, the Graphical User Interface that we are used to, with buttons, images, a mouse, a touch-screen, etc. On Linux and MacOS we can use the default Terminal app, on Windows there is _Windows Powershell or PUTTY.

The command line is also how we communicate with computers that don’t have a screen and/or are far away, like servers!

Before the democratisation of home computers and the subsequent invention of the Graphical Interface, all tasks performed on the computer were executed through text command. Actually clicking on buttons, menus and folders is just a “user-friendly’ layer hiding what is really going on. Every “click / tap” triggers a command, or a series of commands to the computer too, we just don’t see the text anymore.

Termux is also a command-line interface but for Android phones. Because we are trying to turn our phone into a server, which is not its main function, we have to do it directly by typing command in a Terminal window, which is why we install Termux.

Install Termux

Facilitator

This is the part where it gets practical. Depending on the level of comfort with technology, each participant/ group of participants should have their own Android smartphone to follow the instructions. They should be connected to the Wi-fi. It’s easier if they can scan the following QR / type the url to access the page. That way they can also copy-paste some commands and follow the links.

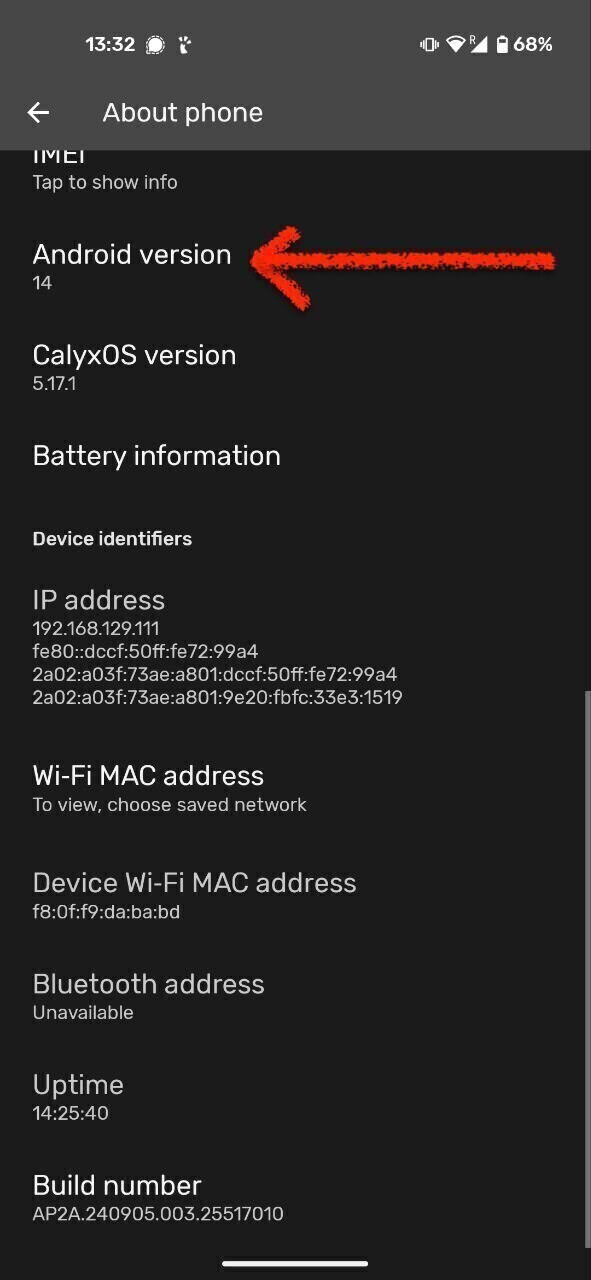

What is my Android version?

To install the correct version of Termux, we first want to determine our phone’s version of Android (the operating system that runs a smartphone).

- Go to your phone’s Settings, all the way to the bottom and look into About phone.

- You should find a line with the Android Version.

Too old for Termux?

If your phone runs Android 4 or less, then this tutorial with Termux won’t work. But there are other ways to give this smartphone a new life, see the Alternatives section.

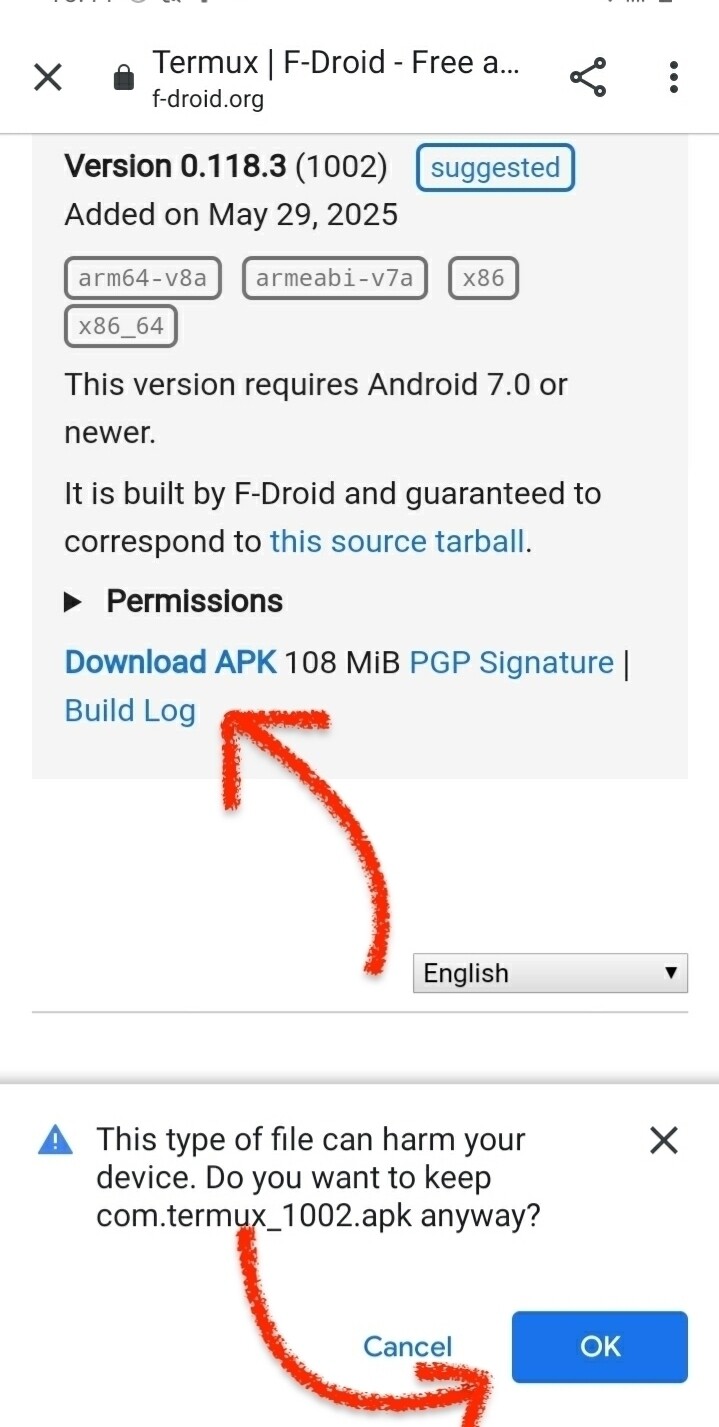

Go to F-DROID

We will download Termux via F-Droid. F-Droid is an App store with only open-source apps. That means their code is visible to everyone so they aren’t any hidden trackers collecting your data.

No Google Play Store

While, you can also find Termux in the Google Play Store, it won’t work the same if you download it from there.

-

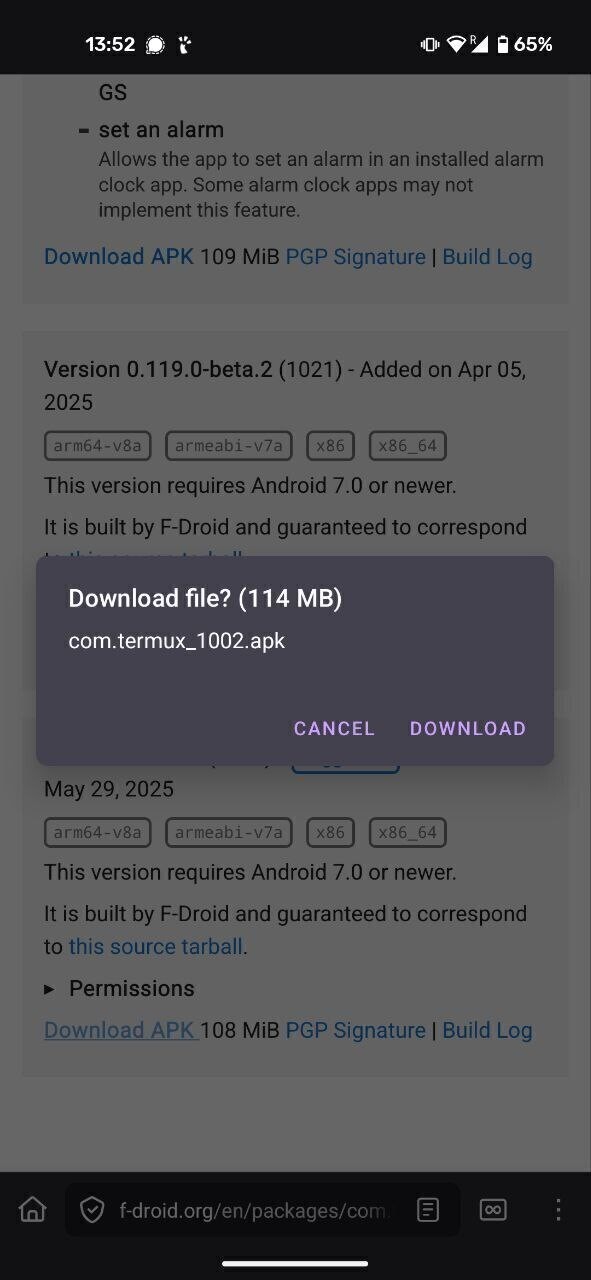

Go to Termux | F-Droid - Free and Open Source Android App Repository or download F-droid and then download the app from there.

-

Scroll all the way to the bottom: Download the stable (suggested) version (not beta) by selecting

Download APK. !!! warning “Android 5 or 6” If your phone runs Android 5 or 6, Download the universal package from here (selecttermux-app_v0.119.0-beta.3+apt-android-5-github-debug_universal.apk) -

Once downloaded, tap the APK on your device. If you don’t find it go to your Files app, under Downloads.

Malicious app?

Your browser might give you a warning about .APK being dangerous. No need to freak out! APK is just a type of file that installs an app, simply be cautious where it comes from, just like anything you download off the internet.

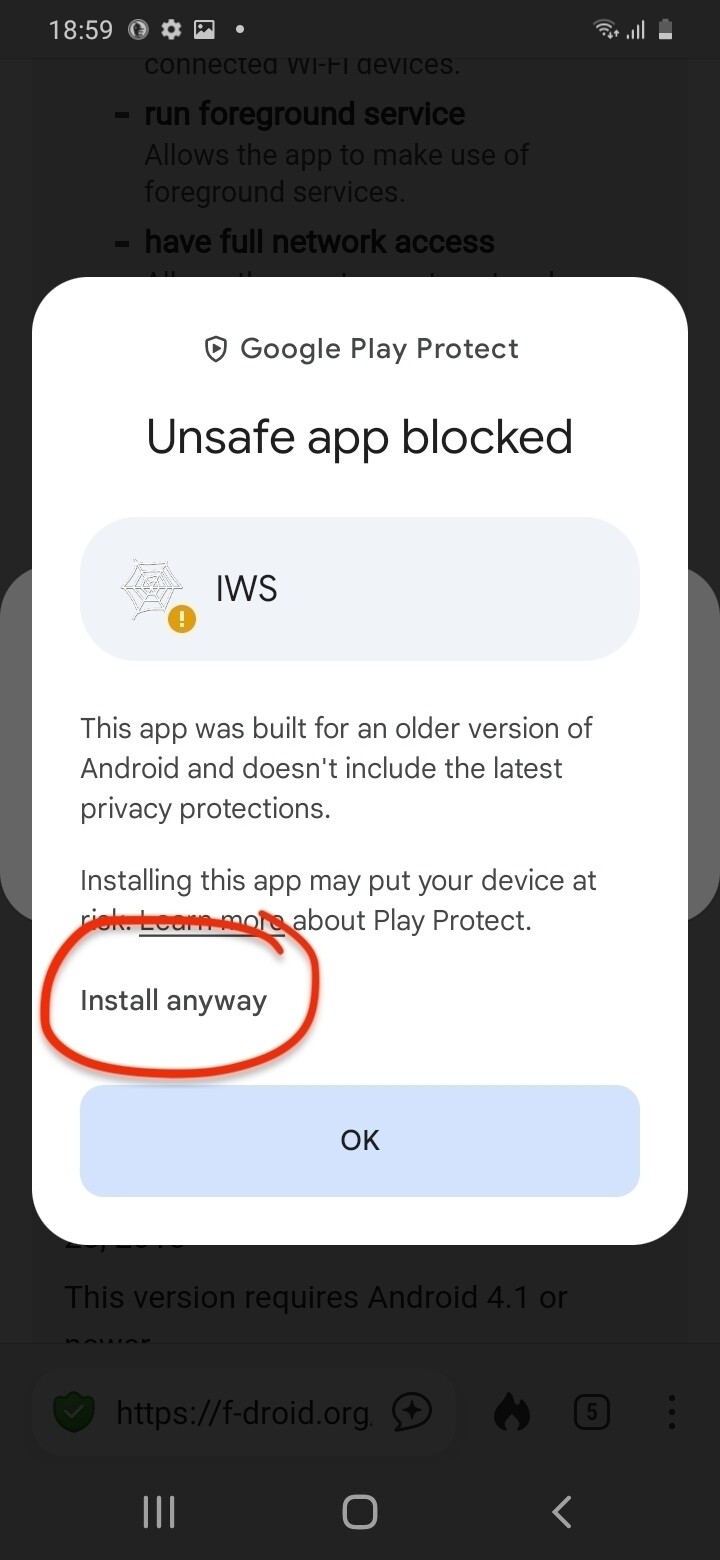

- Click install and accept.

- Tap allow installation of apps from unknown sources (you will need it for later) or go to the phone’s Settings to enable apps to launch from third-party apps and go back.

- Once installed, you will see the Termux launcher on your home screen and in your App Library.

Install Termux API (optional)

Facilitator

Termux API is optional, and is not useful if we are only making a web-server for demonstration purposes. With a more general audience it might be better to skip it.

For more advanced uses, Termux works best in combination with its sister app, Termux API Termux API allows you to control some of the phones’ hardware features, such as vibration, the camera, etc. Find documentation here.

If you would like to install Termux API, follow the instructions here before continuing to the next step.

Last configuration

Before we can start giving commands to our phone via the Termux Terminal, we make a final configuration for storage. Set-up Termux storage helps keep track of your files and folders (more info here)

Note

For every command, follow the same instructions as before: type the exact command, press enter, and wait.

- Make sure everything is up to date (package update and package upgrade)

pkg update && pkg upgrade -y

- Setup storage:

termux-setup-storage -y

- Allow access of Termux to the phone storage, photos, etc.

Known bugs

On some old Samsungs, the text we were typing in Termux wasn’t showing up. We simply downloaded a free and open-source keyboard app on F-DROID called Simple Keyboard instead of Samsung’s built-in version and using that fixed it!

Break time?

If we didn’t do it before, this is a good moment for taking a break, and catch up with the participants running into issues.

My phone as a web-server

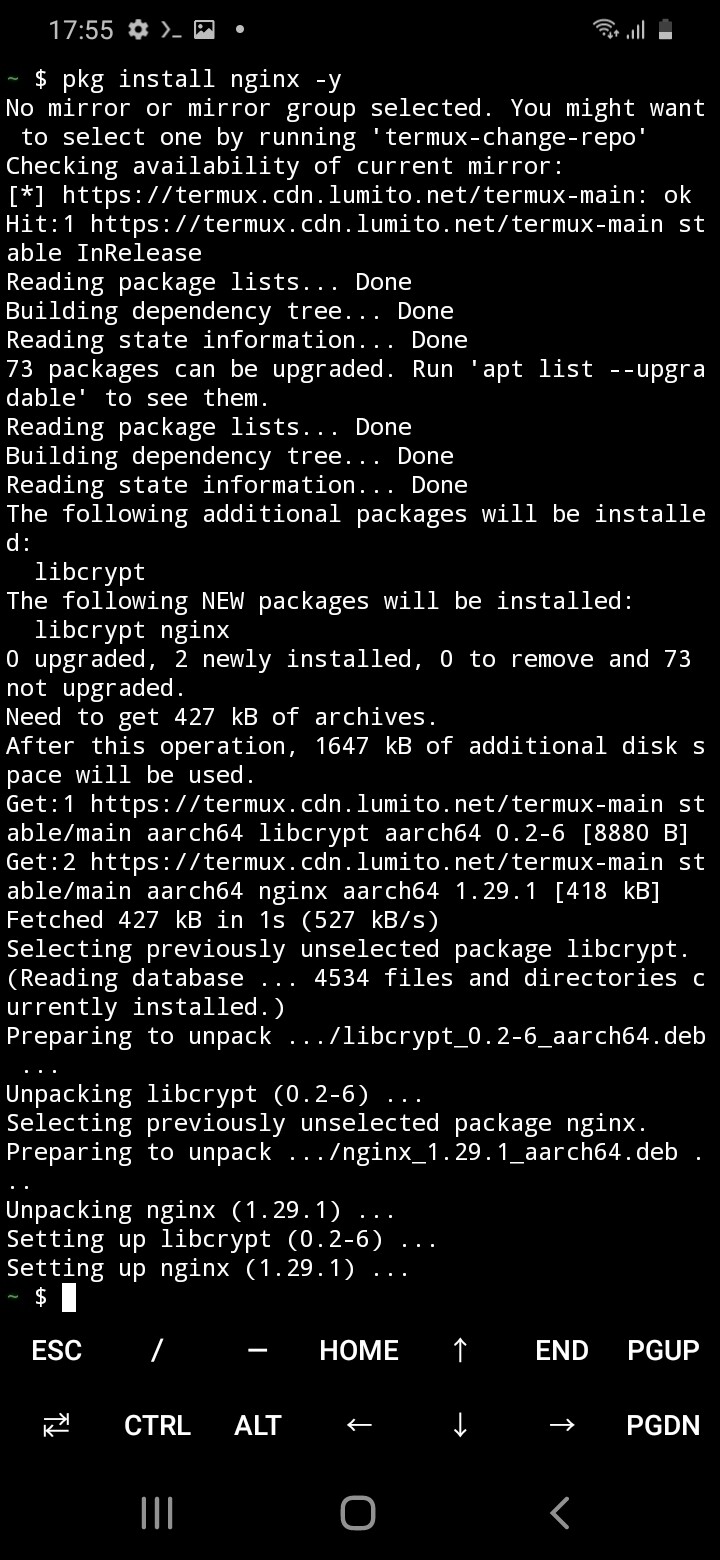

Installing a web-server

Now that Termux is installed, we can give instructions/commands to our phone outside of the existing apps. To make a server, we need a webserver software, a package of code that can receive request from clients (other computers) and send back web content. We will use NGINX {‘Engine X’}, which is widely used.

Downloading NGINX and running it

Open Termux on your phone, type + enter the following and wait:

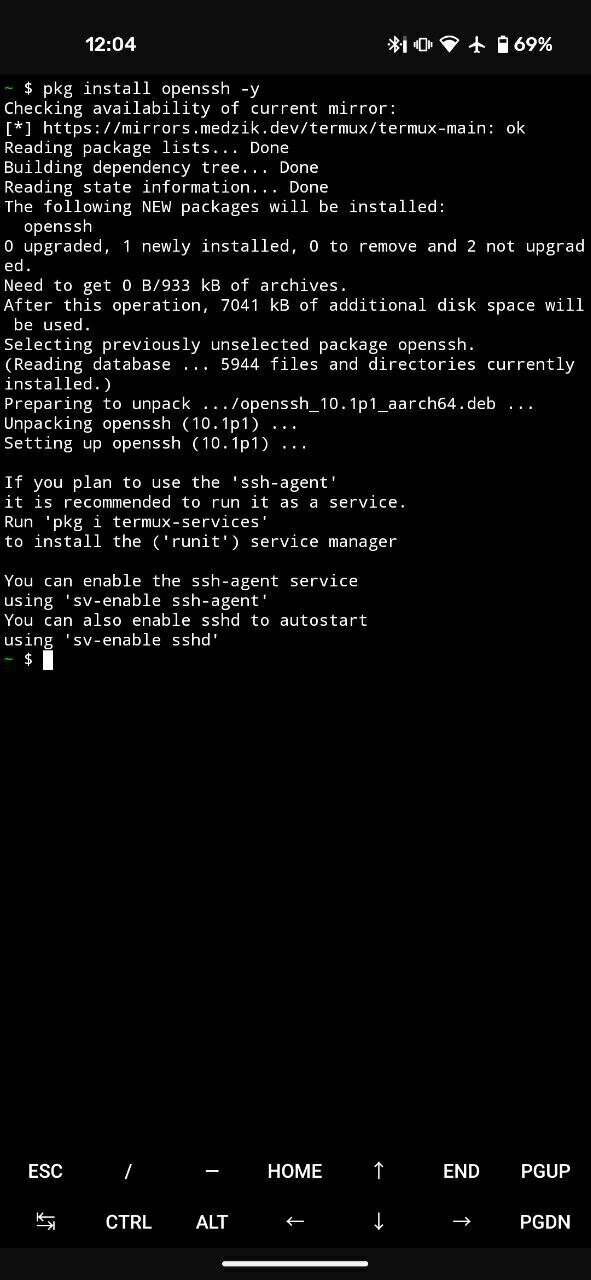

- Install nginx

pkg install nginx -y

Why a -Y?

In the command above, we use the option -y. It stands for “Yes”, which means we want to accept all the configuration questions, instead of manually typing “Y” + enter for each prompt.

- Start-up NGINX with this command.

nginx

Although nothing shows up on your phone (except if you have an error), you server should now be running in the background!

Some helpful commands when working with NGINX

- Stop the server;

nginx -s stop - Refresh the server (its contents):

nginx -s reload - Find help

nginx -h

Is my server serving?

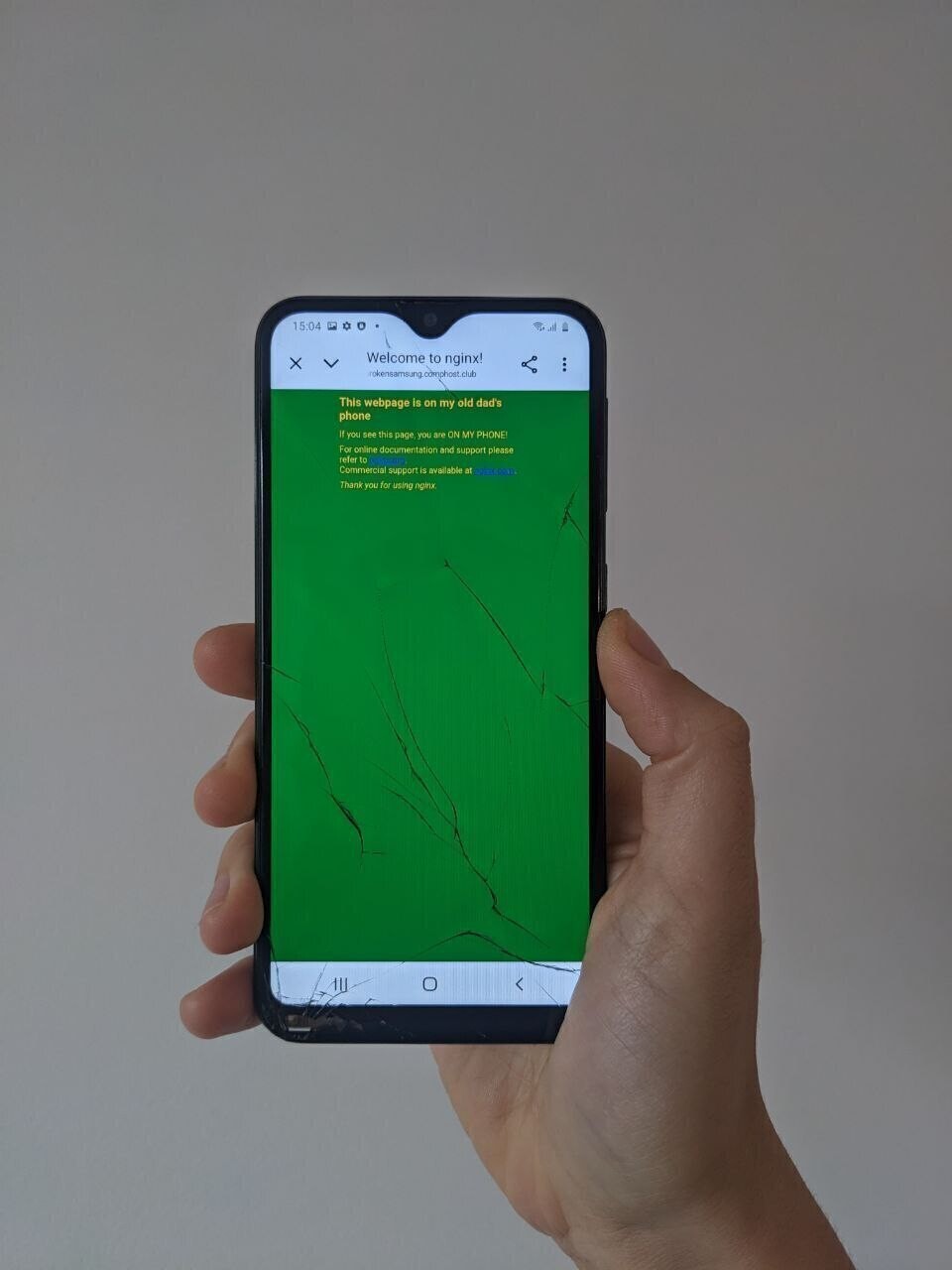

To check if you server is running, open your browser app, and type the following into the search bar: <http://localhost:8080> and press enter. You should see the NGINX default page pop-up saying “Welcome to nginx!”

Now, let’s customize this default webpage.

common mistakes

- I didn’t add http:// in front of

localhost:8080 - I used https instead of http

- http://127.0.0.1:8080 will also work!

A webpage of one’s own

Facilitator

Here it might be nice to take a collective moment to explain what we have done: the server is live but we are simply accessing the webpage file from the nginx folder locally. This is why it’s called “localhost”.

Now that our server is live, let’s understand what we are seeing. When we open a website in the browser, we are actually getting a file from the web-server’s folder on that computer.

Essentially, a website is just a folder made of different file types on a remote computer.

Usually the main file composing a webpage is called index.html. index because it’s a list of all the content of the page, but also all the external resources needed to display the page, such as images, videos, fonts, etc. HTML (Hypertext Mark-up Language) is the programming language used for webpages and the main file format. There are also other languages:

- HTML is made to structure content and give it hierarchy.

- CSS is for styles: the layout appearance of our webpage (colour, size, creating columns, etc.)

- Javascript (

.js) is for interactivity: animating and toggling buttons, dropdown, get remote content, etc.

Facilitator

The explanation above could be demonstrated by making notes on a white board or hooking up a laptop to a beamer and opening a website’s developer tools: right click > view (page) source. An other tab opens with the HTML file of that page.

Our custom webpage

Finding our webpage

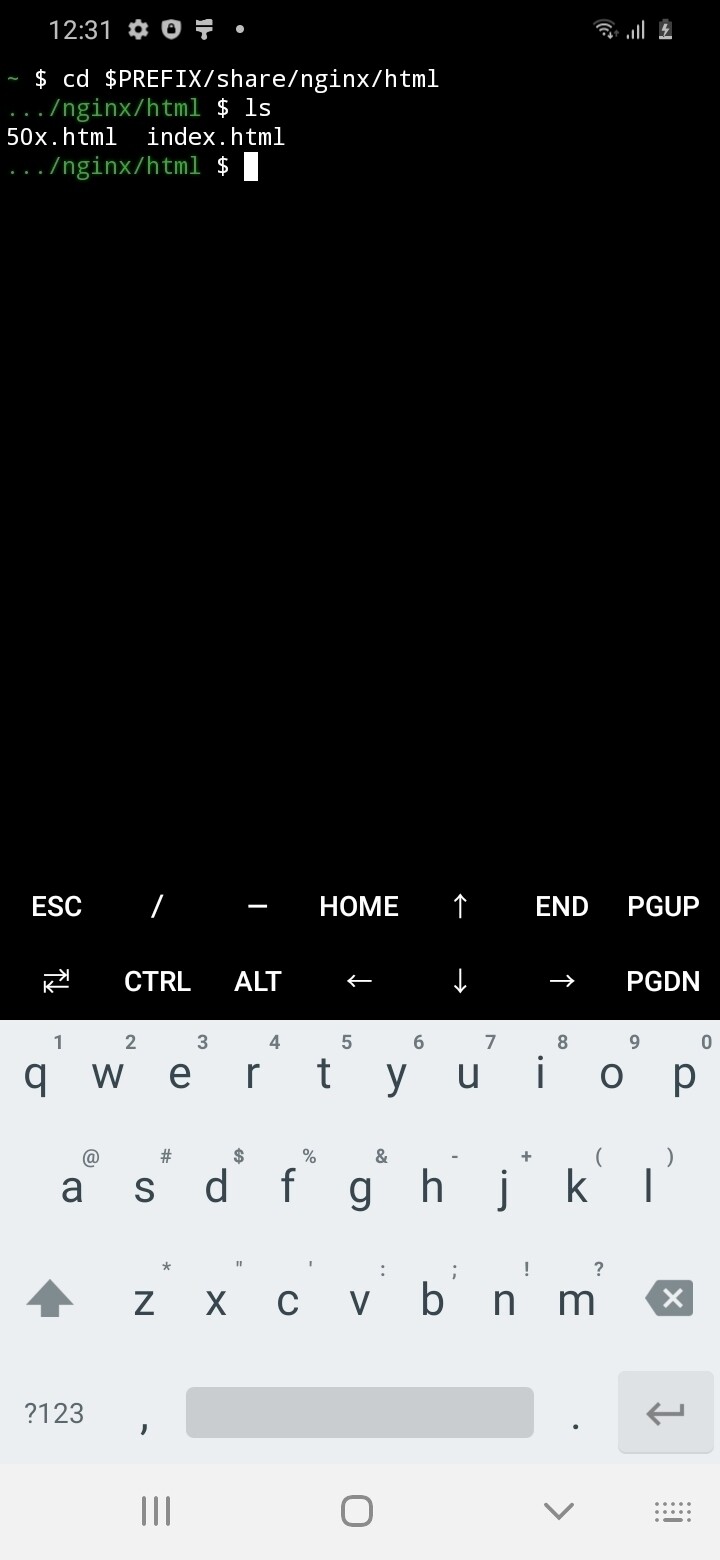

Let’s locate our webpage on our phone. We will navigate through folders using Termux. We use the command cd path/to/folder/ to get to our website folder, created by our webserver. cd stands for “change directory” (directory is another word for folder).

- Type + enter

cd $PREFIX/share/nginx/html

- Now you want to list what is in this folder, using

ls, which stands for “list”.

ls

- You should see 2 files:

index.htmland50x.html.index.htmlis the main page while50x.htmldisplays if there is a specific error.

Note

That means our index.htmlfile is in the folder html, which is inside the folder nginx, which is inside share, etc.

folder location

$PREFIX/share/nginx/htmlis an alias name for the path, a shortcut. For the full path to get to our webpage location is –> /data/data/com.termux/files/usr/share/nginx/html/

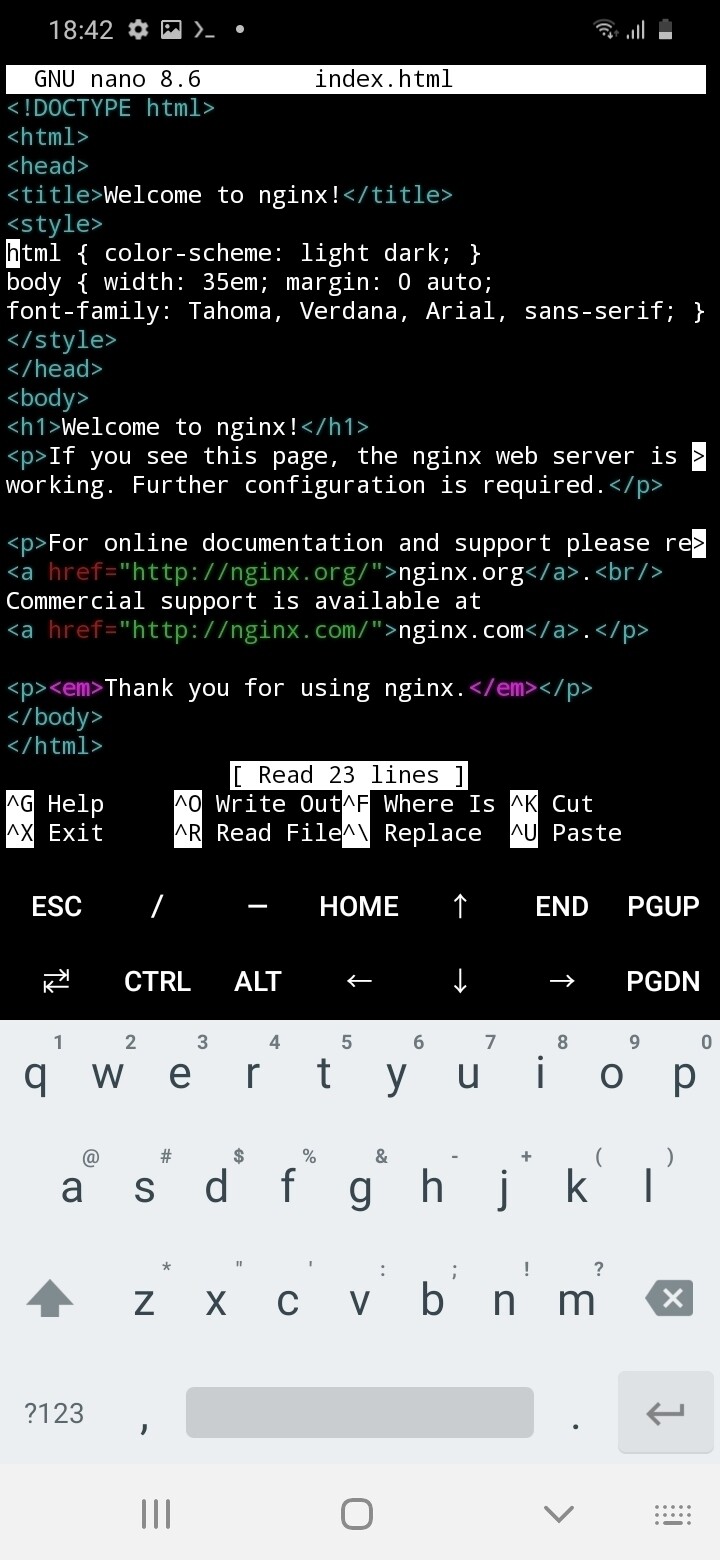

Viewing our webpage.

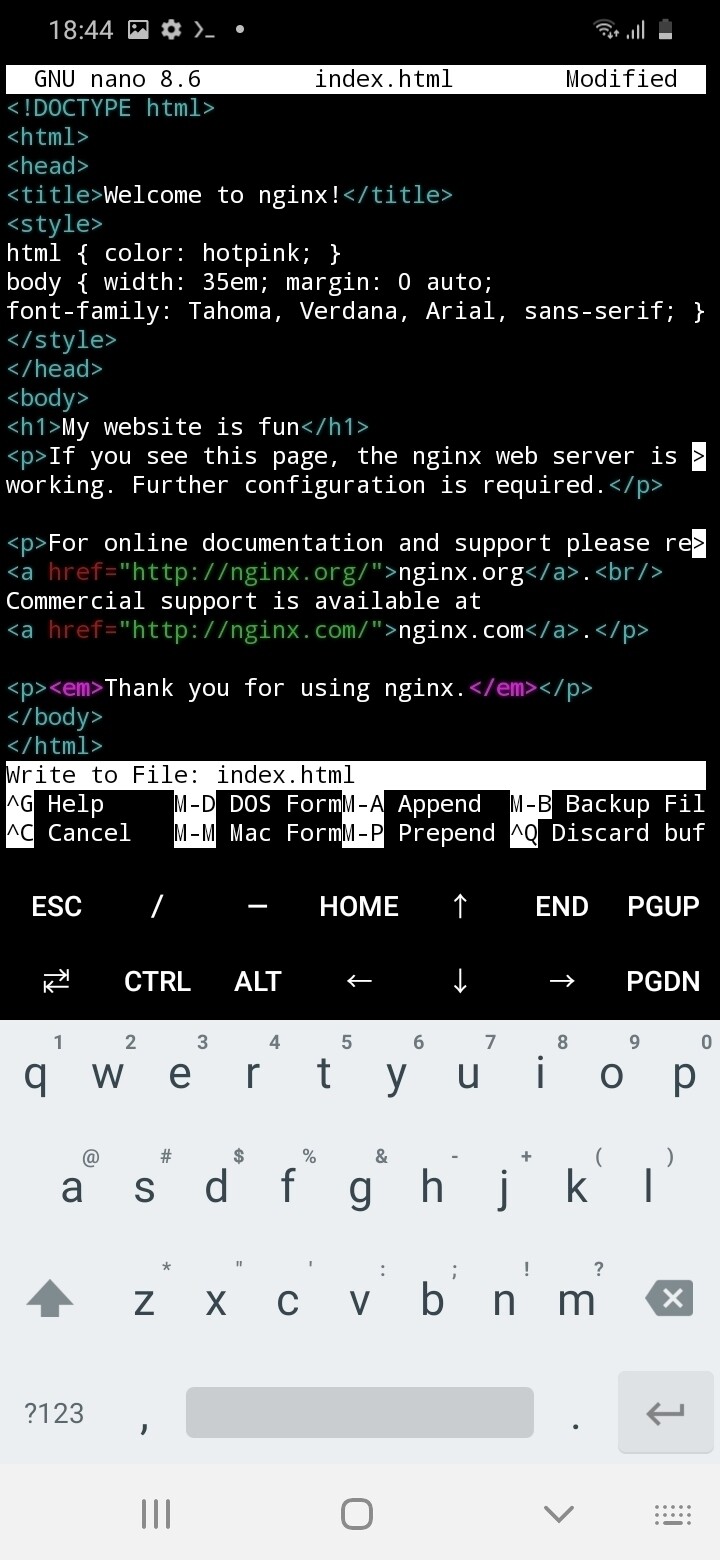

index.html is the webpage we see in our phone’s browser. Let’s open it.

- We use the command

nano file-name.extension. “nano” is a very basic text editor in the terminal.

nano index.html

- We have opened the html file in the terminal. Similar to opening a .docx file in Office.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

<style>

html { color: dark; }

body { width: 35em; margin: 0 auto;

font-family: Tahoma, Verdana, Arial, sans-serif; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome to nginx!</h1>

<p>If you see this page, the nginx web server is successfully installed and

working. Further configuration is required.</p>

<p>For online documentation and support please refer to

<a href="http://nginx.org/">nginx.org</a>.<br/>

Commercial support is available at

<a href="http://nginx.com/">nginx.com</a>.</p>

</body>

</html>

Facilitator

The information below should be explained while showing the html excerpt on a beamer or drawing on a white board. More info about HTML here.

HTML structures information with different value inside “elements” surrounded by <tags>: opening tag <p> and closing tag.</p>. Here we see several elements, that we find back on the rendered browser page. Inside the <body> element, there is an <h1> tag with a header, some <p> paragraphs, and some <a> links.

Inside the <head>, we find information regaring the page but that isn’t the content:

<title>...the title here...</title>: is the title that shows up in the browser tab.<style>color: blue;<style>is where we put CSS code to give information about the layout, color, etc.

Lazy typing

We can use the tab button (with 2 arrows) to autocomplete a file or folder name. start typing “inde” and tap the tab button, it will automatically fill in the end of your file name “index.html”

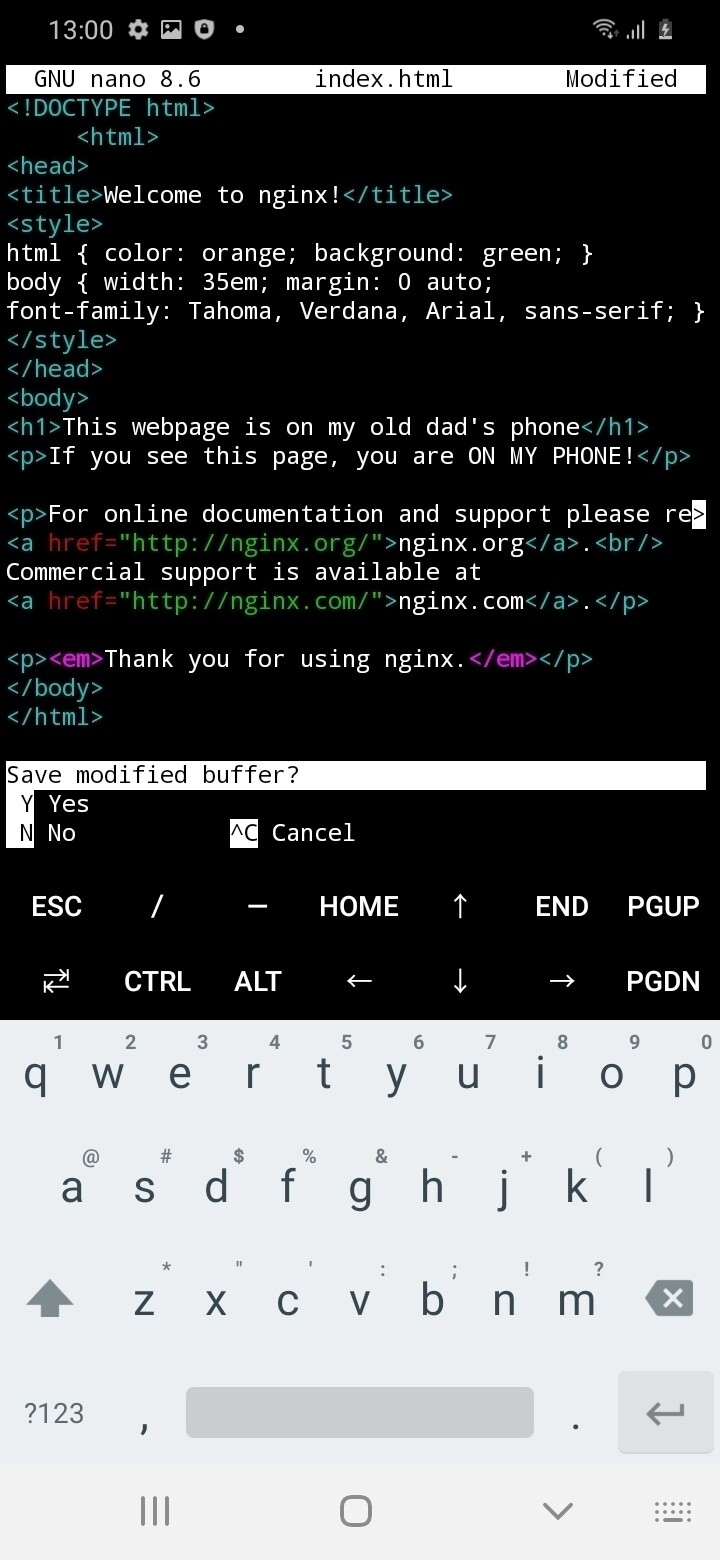

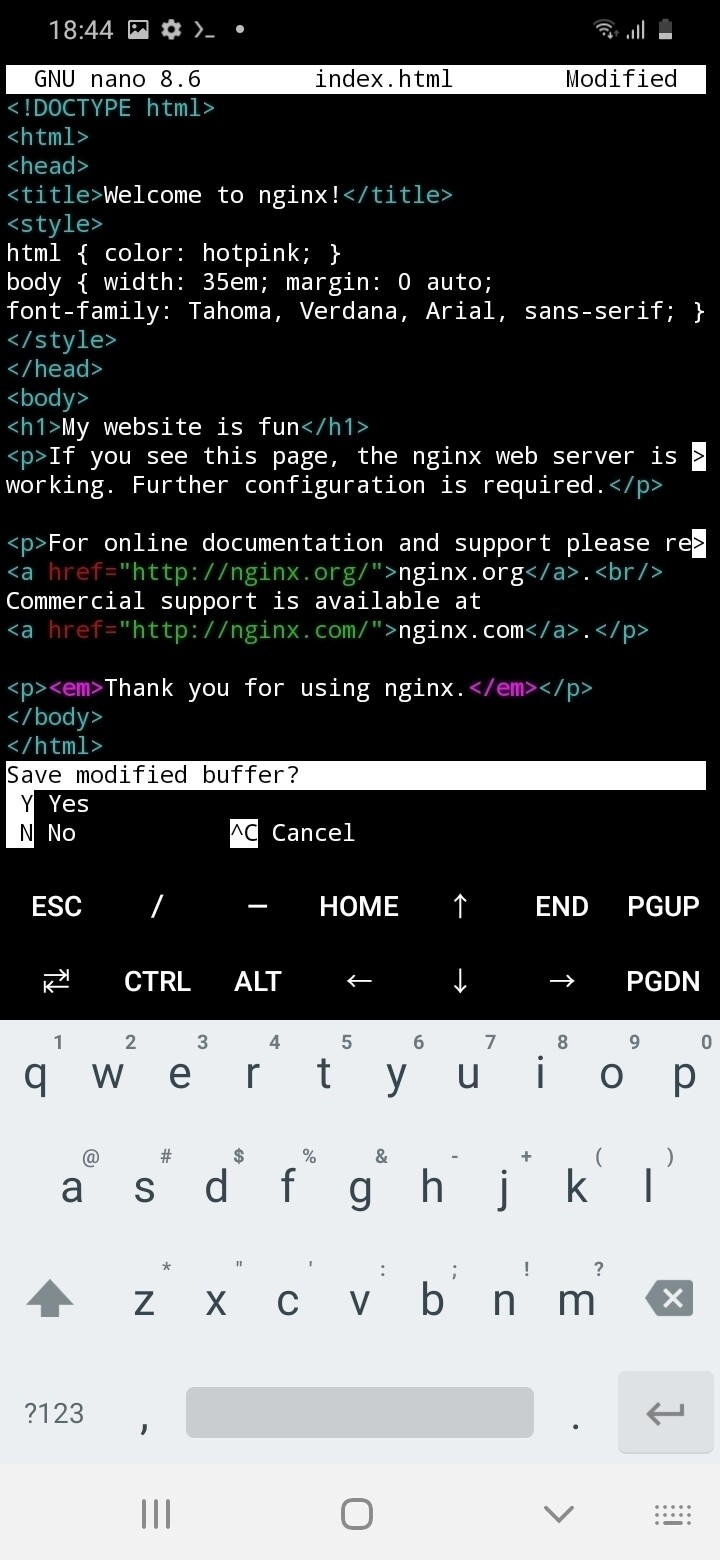

Editing our webpage.

Let’s change some text inside the page.

Facilitator

This moment is creative, let every paarticipant choose their own text, their own color (look at CSS colors) in a few minutes.

- Using the < > arrows in nano, navigate and change some text.

<h1>This webpage is on my old dad's phone</h1>

<p>If you see this page, you are ON MY PHONE!</p>

Put me inside those tags

Make sure you respect HTML syntax. Elements should be within tags <h1>Your text here</h1>

- Change the text color in the

<style>

<style>

html { color: orange;

background: limegreen;

}

</style>

Styling with style

Make sure you respect CSS syntax. The style info should be within <style> Styling goes here and ONLY here<style>. Each declarations follows this structure: property : value;, for example: font-size: 20px;

HTML guides

More information on HTML on the official W3. Make you own websute guide, HTML section here, HTML webzine here

CSS guides

This great CSS resources by artist Doriane Timmermans: declarations.style or this video

Save, quit and reload

Now, let’s save and see our update:

- tap

CTRLand typexin Termux’s keyboard. - You will get the question “Save modified buffer? [Y/n]”

- Type

yfor yes and press enter. (Typenoto quit without saving). - Go to your browser and refresh the page [http://localhost:8080/index.html].

Can’t see any changes?

If it’s not working, try the following:

1. Shut down the browser app, reopen it and try again.

2. Start nginx again, in Termux nginx -s stop, then nginx

3.Check that you have effectively made and save changes in the index html page: nano index.html

Nginx error

Here add nginx path routing issue fro samsungs (@ibo or Rein)

Ok, great! But that’s no so exciting is, it? I can view my webpage on my own web-server machine. I could also just open that file in the file manager, I don’t need to web for that. Actually, your webpage is already accessible by other clients (other computers), you just need to give them your IP address.

Where does my server live?

Facilitator

Before we actually visit webpages of other participants, we introduce the concept of IP address, by drawing a metaphor between an IP address/ web address and a street address. This helps reminding of the physicality of the web: websites are inside servers that are somewhere in a building in the physical world.

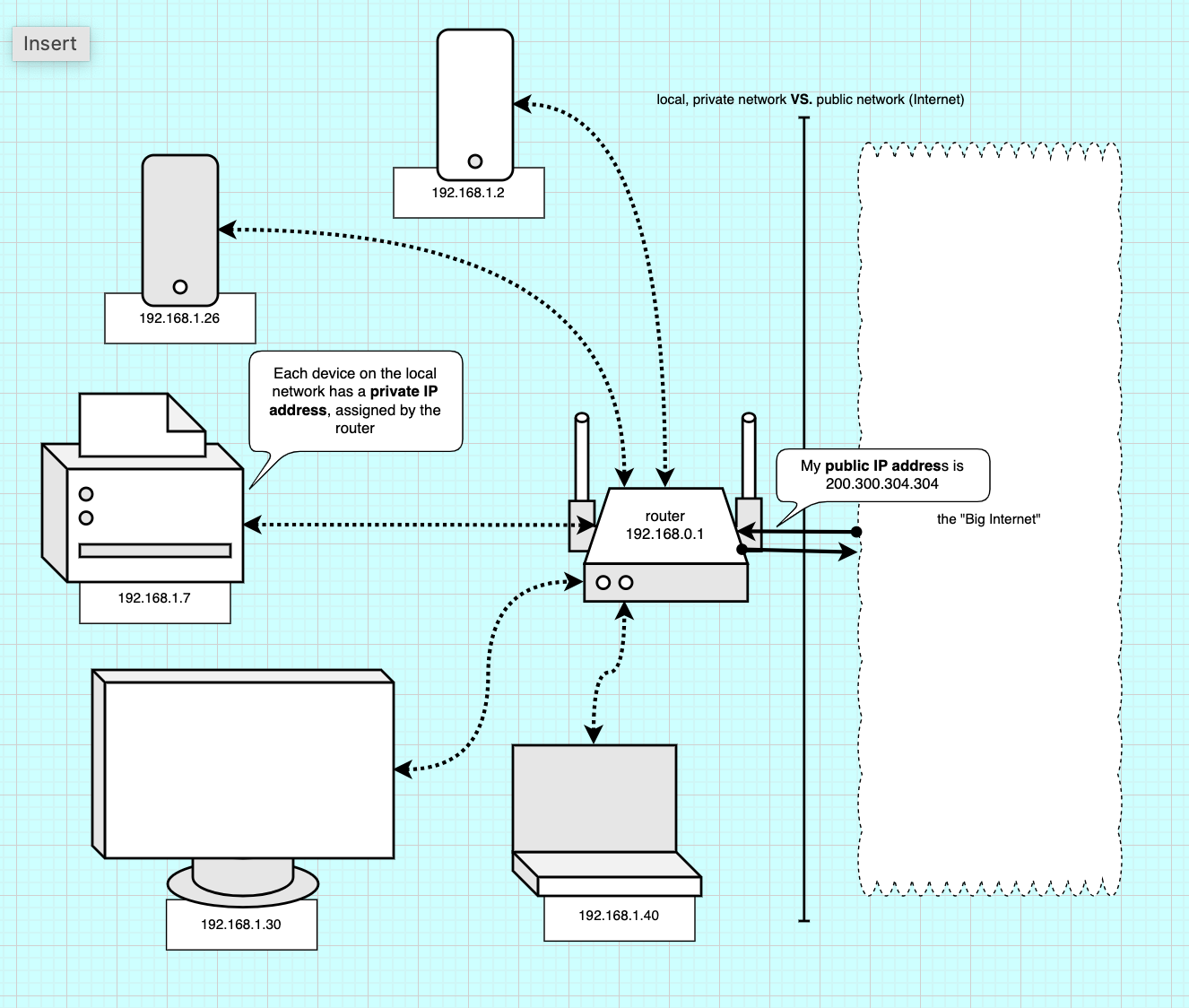

WTF is an IP address?

IP address stands for Internet Protocol address, which is the method of communication used by all types of computers/servers across the internet (web-servers, emails, file transfers, etc.). Since the internet is a massive network of computers, we need a unique way to identify each server, so we can send requests to it and the server can send information back to the correct device.

Think of it like a street address: each IP address is unique and is a way to tell where that servers “lives” and how to get there.

Traditionally IP addresses are made of a series of four sets of numbers (0 to 255) separated by a period. Therefore there are addresses ranging from 0.0.0.0 to 255.255.255.255, that’s over 4.3 billions unique addresses! However, with the exponential rise of devices connected online, we are starting to run out of addresses to give away, which is why some devices now use a new longer IP address format called IPv6 (it looks like that: 2600:1f1c:446:4900::259)

Local vs. Global network

Facilitator

Going back to the tutorial, we find out every phone’s IP address, but first realising what a private IP address is vs a public IP address.

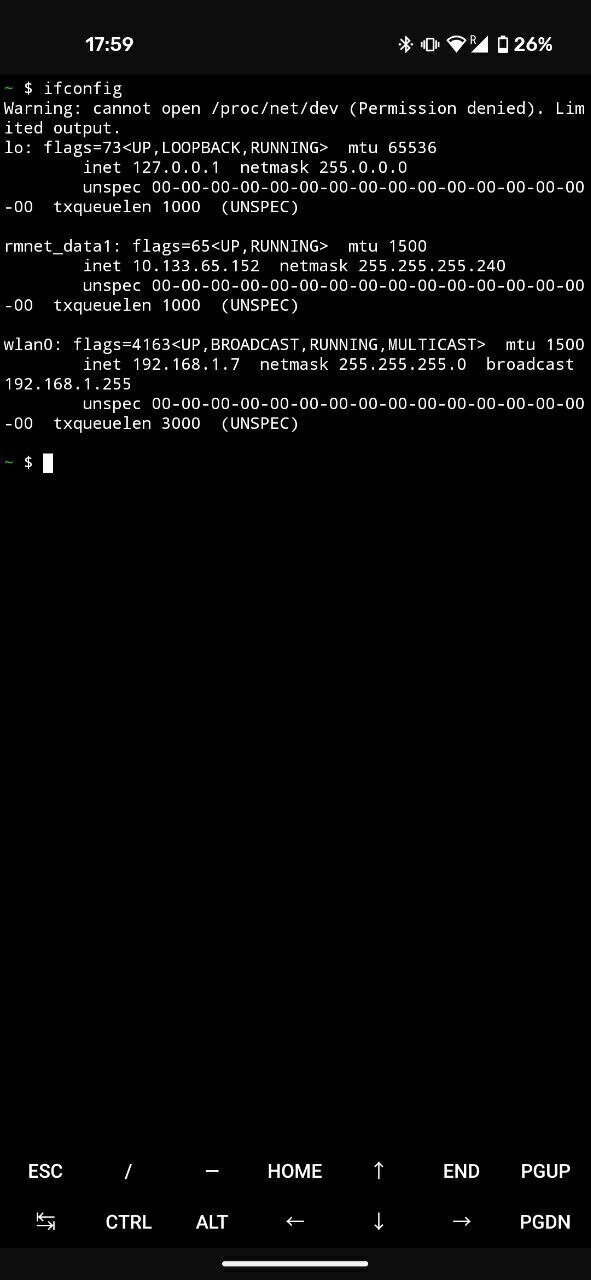

What is my server’s IP address?

In Termux, there is a command to determine the current IP address of my device. We use the command ifconfig to test the reachability of a server.

- Type and enter:

curl ifconfig.me

- We get something like this:

200.300.304.304

Facilitator

By asking everyone to write down and read this IP address, we realise everyone has the same. We explain why (below):

Now, everyone phone that is connected to the same wifi should get the same address. Why is that? This is actually the Wi-Fi router’s public IP address, which is the unique address used by the router to access the Internet. All the requests we make to remote servers (through the internet) travel through our wi-Fi router, which is the gateway to the big internet, the global network.

However, all the devices connected over Wi-Fi or cable to the router also form a network: the local network. If you played multiplayer videogames in LAN (Local Area Network), like having a minecraft server with your friends at home, it might be familiar. This local is also how we can talk to our printer remotely, while we are connected the same Wi-Fi network.

In this local network, each connected device also has a unique IP address, so the router knows who is sending requests (to the internet or to other devices) and can direct the trafiic. This local IP address is called the *private IP address.

In short of public IP address is the address of our router when it’s browsing the internet, while a private IP address is the local address of each device on our home network.

Facilitator

The image avove helps explain the concept of local network. Each device on the local network is connected to the router over Wi-Fi (wireless) or cable (ethernet). To tell each device apart and receive requests the router assigns a local IP address to each device. All the requests go through the router, either to talk in between device (e.g.a computer sending files to print to the printer) or through the “gateway”, to the biginternet and back.

What’s my phone’s private IP address?

In the terminal we use ifconfig to know our device private address:

- Type and enter:

ifconfig

- In the output we look for the line starting with

wlan0....inet, this relates to the Wi-Fi interface. Afterinet, there is an IP address that should look like:

192.168.1.255

- Write this address down. This is your devices IP address as long as your remain connected. (It might change if you disconnect then reconnect).

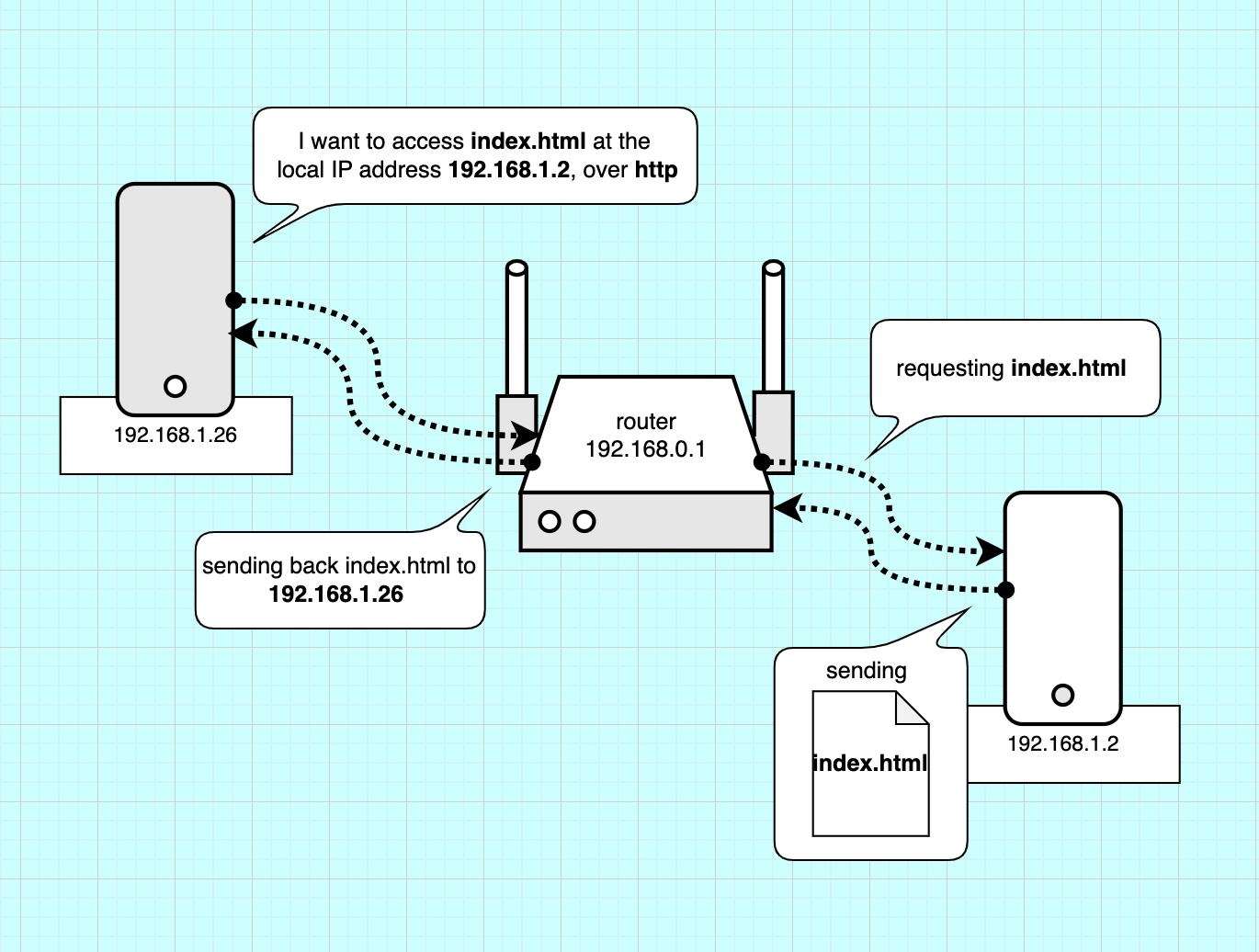

Browsing the local network

Now that we know our web-server local (private) IP address (where our server lives), we can let other devices on the network visit our webpage!

Facilitator

Now, we can start visiting each participants’ custom webpage. With a laptop connected to the Wi-Fi and a beamer, we cn each participant for their “address” (IP address), type it in and show it to everyone!

- Using another device than your phone server, visit your phone’s servers over the local network.

- In the browser type + enter:

http://+192.168.XX.XX+:8080 - Make sure you use http:// and not https:// (we don’t have the secure SSL certificate yet).

- You can now view your custom webpage.

Facilitator

We can now explain what is going on more precisely. Our client (phone or laptop) is requesting the index.html to a certain address. The router is redirecting this request to the phone server (with its local IP). The server “serves” the index.html file.

Facilitator

This local area network already holds a lot of potential. Knowing we can do that, a lot of uses of the internet could work just as well with a local network, without the need of a datacenter. For example, a restaurant’s QR code menu could be on the local network, same for local news, etc. That way data wouldn’t have to be stored and travel from a remote location. The image above shows a project by Constant VZW (BE): they have a local netwrok to take notes during a meeting or a workshops. Instead of having the notes in a remove server, they host it here. That also makes sure they remain private, since it’s only accessible if your are within the Wi-fi’s range.

Facilitator

We can ask a question to the participants to open up a discussion: what uses of the Internet could work a local network? what new uses could you imagine?

Going online in the big Internet?

Facilitator

After understanding the client vs. server relationship, we dive in the bigger internet.

While a local network already holds potential, the ultimate (at least the original) goal of the Internet is to connect remote places and give users access to information all over the world.

There are several ways to open a local server to the public over the Internet. Essentially it consists in explaining to other servers at which public IP address your website can be found so visitors can be directed there.

Protip

We already know our router’s public IP address from earlier. However, for security reasons most internet providers don’t keep a fixed IP address for each house network and opening our private network to the internet expose us to security risks. However there are many tutorials online on how to achieve that, depending on the internet provider/ router you have.

What about my website’s name?

Wait a minute! When we I go online, I never use an IP address. I just type an address in the search bar, or look for it with a search engine. Indeed, since IP addresses are hard to remember and change (for security reasons or because a site moves from 1 server to the other) we use domain names in web addresses.

A domain name is made of at least two parts: the domain name, like Wikipedia and the extension, like .org, or (.com, .net, .nl, .fr, etc.). Sometimes there is also a subdomain like in

www subdomain

Most website use the default “www” as a subdomain, as in

Facilitator

The image above explains how we can retrive a webpage over the internet. First our request goes via Wi-Fi to our router. The router has to figure out what IP address corresponds to the domain name. It sends a search via a DNS, Domain Name Server: this server can match IP addresses to domain names and sends back the IP address of the server. The router can then request the files to the server, which serves them (sends them back). More info on this nice comic book: How DNS works.

Facilitator

The 2 exercises below are optional, depending on the grounp/ level / timing. The idea is to associate IP address to domain names

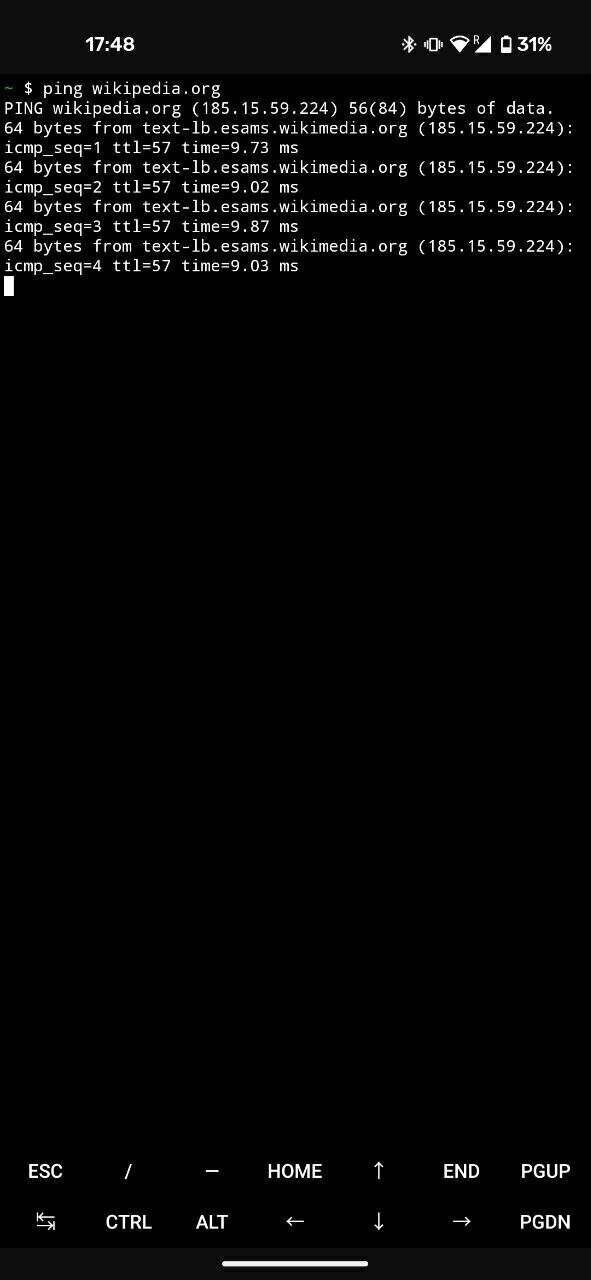

Exercise: IP address of famous websites

In the terminal (Termux) we can use a simple command to know the IP address of a website (its server). We use the command ping to test the reachability of a server.

- Type and enter:

ping wikipedia.org

-

If we are connected online, we should now be receiving information back within a few ms of delay! We also see the IP address of wikipedia.org, so

185.15.58.224(last time we checked). Entering this IP address in your browser should get you to Wikipedia too: http://185.15.58.224 -

To quit

ping, tapCTRLandcon the keyboard.

Exercise: Where does Wikipedia live?

Using service like IP location, we can match an IP address to a location and see where famous websites have their servers.

- Go to IP location

- Type an IP address (like 185.15.58.224 for wikpedia)

- Look on the map where it is :)

URL - A webpage’s full address

A url is the name of the complete web-address. It’s made of 3 parts. For example we have https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet/index.html

- https:// is the protocol of communication of the web (webpages in websites, on web-servers)

- en.wikipedia.org is the domain and sub-domain

- /wiki/Internet/ is the path, the folders and subfolders we have to go through to get to the location where our file is.

- index.html is the file we are requesting, the file that contains the content of this page and the list of all the resources needed to display this page (fonts, images, stylesheets, databases, etc.). By default it’s index.html, so no need to write it.

http VS http’s protocol

http:// stands for the communication protocol we are using. http or (https) is the protocol for browsing websites, whereas SMTP is for sending emails, etc. :8080 is our port, the “place” we are trying to access in our server. If our IP address was the address of our server-building, the port would be the floor where “NGINX” has its office.

There are several ways to go “public”: using a fixed public IP address and opening the ports to the public (ports forwarding), using a dynamic DNS tool or using a reverse proxy server.

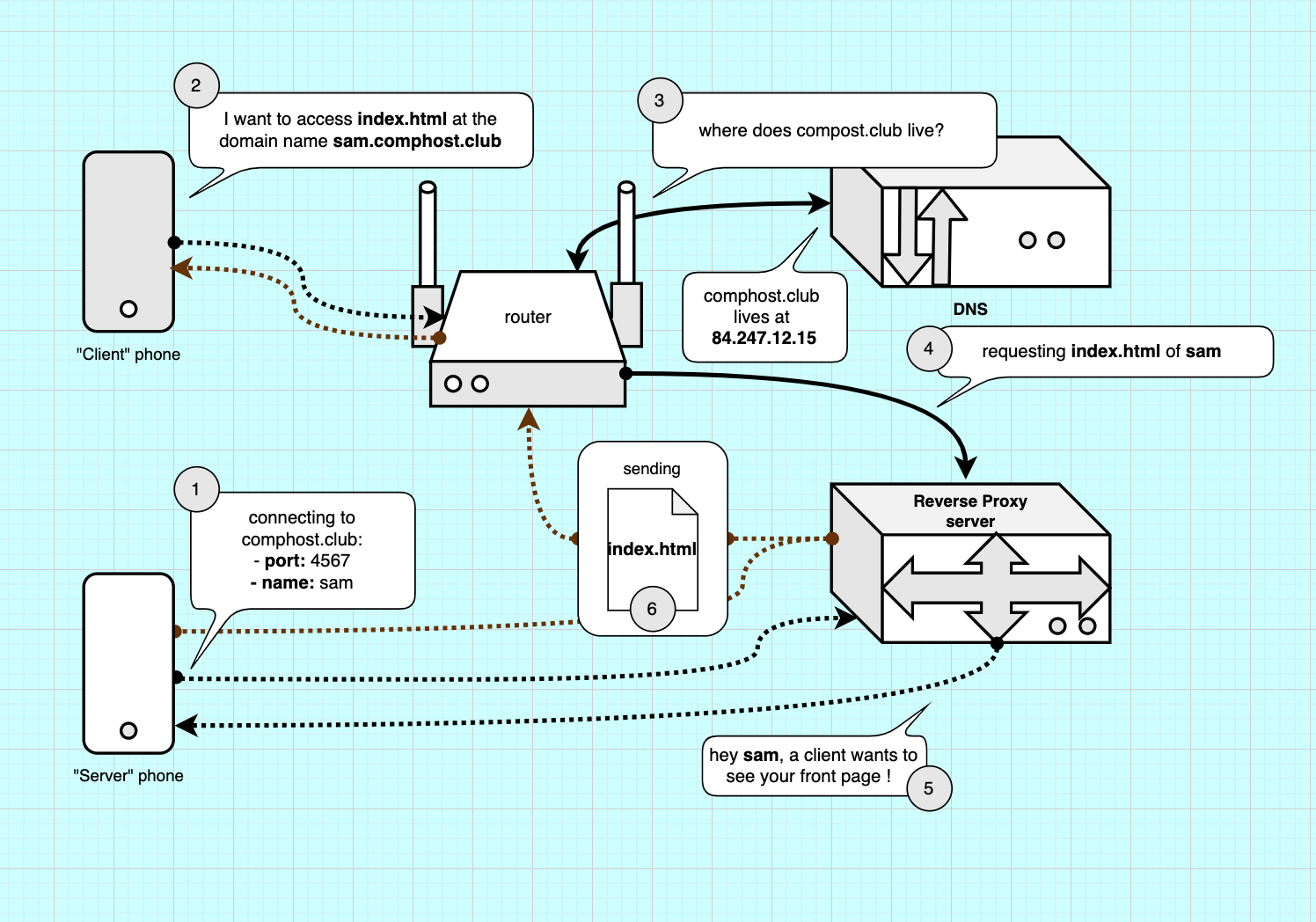

A Reverse-Proxy

We will be using a reverse proxy. A reverse proxy is an intermediate server that is already public and acts as a intermediary between our local web-server and potential clients (other devices).

In this tutorial, we use comphost.club’s reverse proxy server, that is based in the Netherlands, so we can keep this somewhat local.

With the image above we can explain how our reverse proxy works. 1. We create a “tunnel” connection between our server phone and the proxy server. 2. A client tries to make a connection , gets directed to the proxy-servers’s IP address via the DNS (3-4). 5. The proxy server relays the connection to the server and then forwards the response to the client (6). This is similar to how a VPN works, minus the encryption.

Reverse-proxy configurations

Below is outlined several ways to create a reverse-proxy:

- Using SirTunnel on comphost.club, our slef-hosted method.

- Using localhost.run, a freemium online tool with no signup.

- Using Ngrok, a freemium and powerful tool with sign up.

There are many (commercial) reverse proxy tools, some of them are listed in this comprehensive list.

1. SirTunnel on comphost.club

Comphost.club runs the reverse-proxy softare SirTunnel which runs with the communication protocol SSH.

Warning

However, comphost.club domain hosting and reverse proxy are only available on workshops hosted by CCU. Luckily, there are many commercial alternatives. You can also look into self-hosting your own reverse proxy software on your server.

SSH protocol

The Secure Shell Protocol (SSH) is typically used to log into a remote computer’s command-line interface (CLI) securely and to execute commands on a remote server. We can also use ssh to control our phone remotely via a laptop computer, so we can type easier.

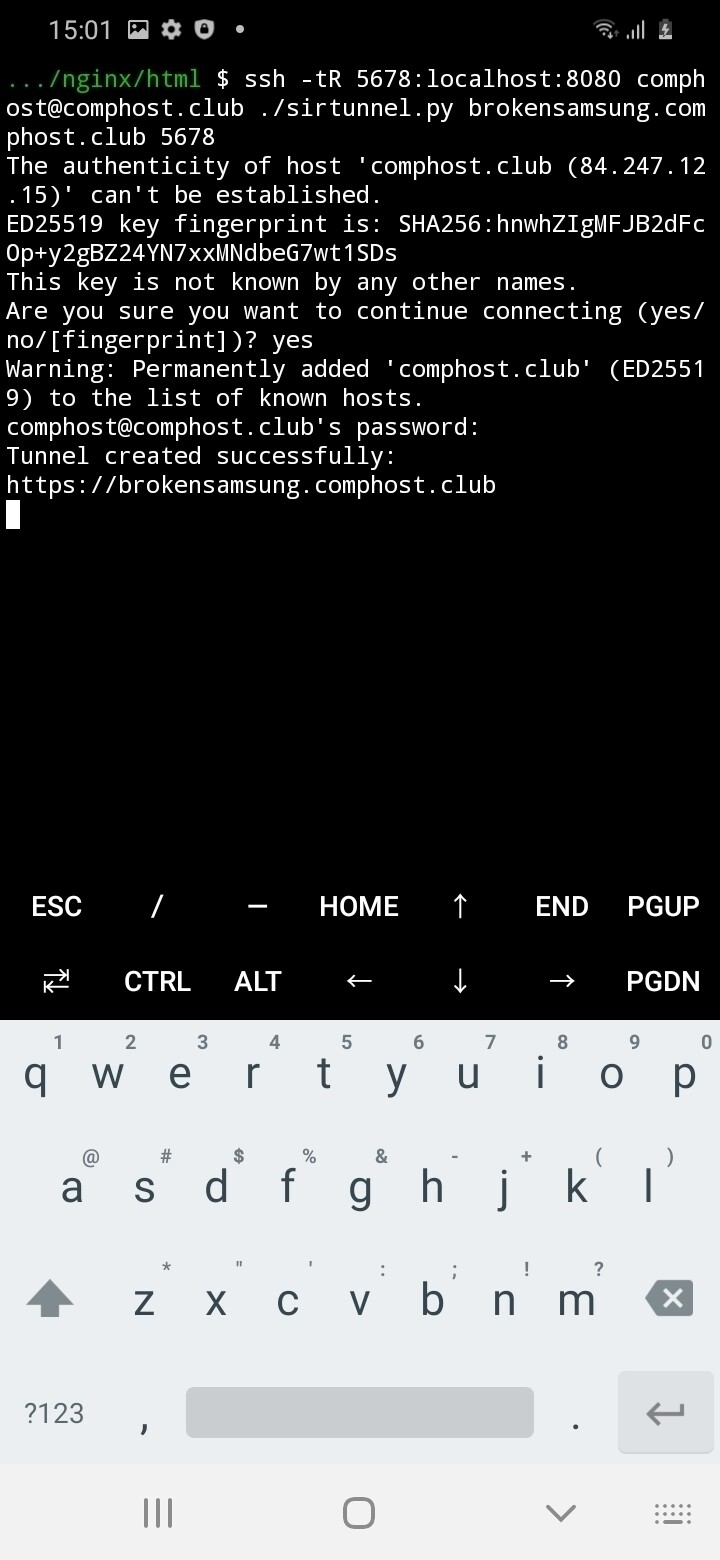

- We install an SSH sotfware in our phone: OpenSSH:

pkg install openssh -y

- We customise our own SirTunnel command based on the following:

ssh -tR XXXX:localhost:8080 comphost@comphost.club ./sirtunnel.py xx-my-subdomain-name-xx.comphost.club XXXX

-

We replace

XXXXby a unique port number (each participant must have its own), for example4567 -

We replace

xx-my-subdomain-name-xxby an original subdomain address, for examplebrokensamsung -

Type + enter the custom command in Termux:

ssh -tR 4567:localhost:8080 comphost@comphost.club ./sirtunnel.py brokensamsung.comphost.club 4567

-

If connecting for the first time, confirm the authenticity of host by typing “yes” and enter.

-

Enter the password and press enter.

Facilitator

password is workshopbymarieandrein:)

Protip

When typing a password in a CLI, you cannot see it. If you are concerned about spelling mistake, type it in another program (your Note app) and copy-paste it.

- Other devices can now visit your webpage at brokensamsung.comphost.club

All the mobile-servers currently up are listed on comphost.club’s index page.

Troubleshooting

Permission denied? Try a different port (this one might be taken)

Using localhost.run

- In Termux, type and enter:

ssh -R 80:localhost:8080 localhost.run

-

Type yes + enter to connect.

-

You will get a temporary domain name to looks something like https://46dd096d0d85c2.lhr.life. If you want to add a custom domain you will have to pay.

Using ngrok

Ngrok is a US commercial reverse proxy tool, so you have to install it, create and account.

- Install ngrok in Termux, type each command, press enter and continue

pkg update -y

pkg install git -y

git clone https://github.com/Yisus7u7/termux-ngrok

cd termux-ngrok

bash install.sh

- Sign-up to ngrok:

- Visit

- Sign-up and verifiy your email address.

- Copy your auth-token in the relevant section and add it to the config: - Enter the following command, replacing [auth-token] by the auth-token you just copy-pasted.

ngrok config add-authtoken [auth-token]

- under static domain copy and paste the command, changing port 80 to port 8080

ngrok http --url=gorilla-champion-tomcat.ngrok-free.app 8080

Check ngrok configuration and paid tiers to get more advanced configuration. For example, to set a custom domain

Conclusion

Facilitator

So this is the end of the guided workshop. It’s nice to take the time to wrap-up this moment part. Some participant might want to leave, while other continue editing their webpage. We can start by asking what are the biggest take-aways for each participant in round of speech. Some nice open questions: Do they understand why is self-hosting important? How would they imagine an internet that ran on tiny reused devices?

The mobile web-server tutorial stops here! Thank you for following it. If you have any feedback or questions, don’t hesitate reaching out (see About page for contact details).

Going further

There are additional resources in the Going further Section. You can also check the Comphost’s Git repository for extra code and examples.

We will be posting some updates as we develop the documentation further.